Financing Commons for Convivial Conservation

Convivial (literally: ‘living with’) conservation offers a new and integrated approach to understanding and practicing environmental conservation. As our current monetary and economic systems are not fit for purpose, we must initiate and create conditions for life as whole and develop a commons-based finance that will make it possible to finance nature conservation and restoration without allowing it to be commodified.

Without nature, we become impoverished as humans and cannot survive. Clearly nature needs to be conserved and in a lot of cases regenerated. This seems straightforward enough, but whoever talks about nature conservation must also talk about inequality – because who owns and has access to land greatly influences who will acquire power and wealth, and who will suffer deprivation and indignities. Similarly, whoever talks about climate must talk about biodiversity because the stability of the atmosphere depends upon a stable biodiversity of species and living systems.

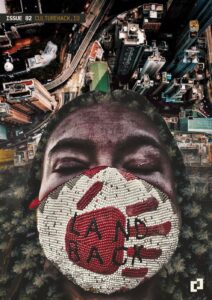

So, when we talk about the connections between inequality, climate, and biodiversity, we must always ask the question: “Who owns and stewards the land?” We must permanently underline the mutual connections because a narrow focus on net zero and energy transition can lead to further destruction of the natural world. And “saving the planet” can actually aggravate inequality if it leads to more centralization of ownership and power. Destruction of the planet can indeed be done climate-neutrally.

“Saving the planet” can actually aggravate inequality if it leads to more centralization of ownership and power. Destruction of the planet can indeed be done climate-neutrally

In most cases, sustainable finance and philanthropy have failed to take a more systemic view of how the health of “nature” is related to other crises, or indeed, to humankind itself. It has become somewhat clichéd to say that humans are disconnected from nature, which is certainly true; modernity’s dreams of progress and globalization have left most of us disorientated and disconnected. The real question is what might we do about this problem.

Where do we go from here?

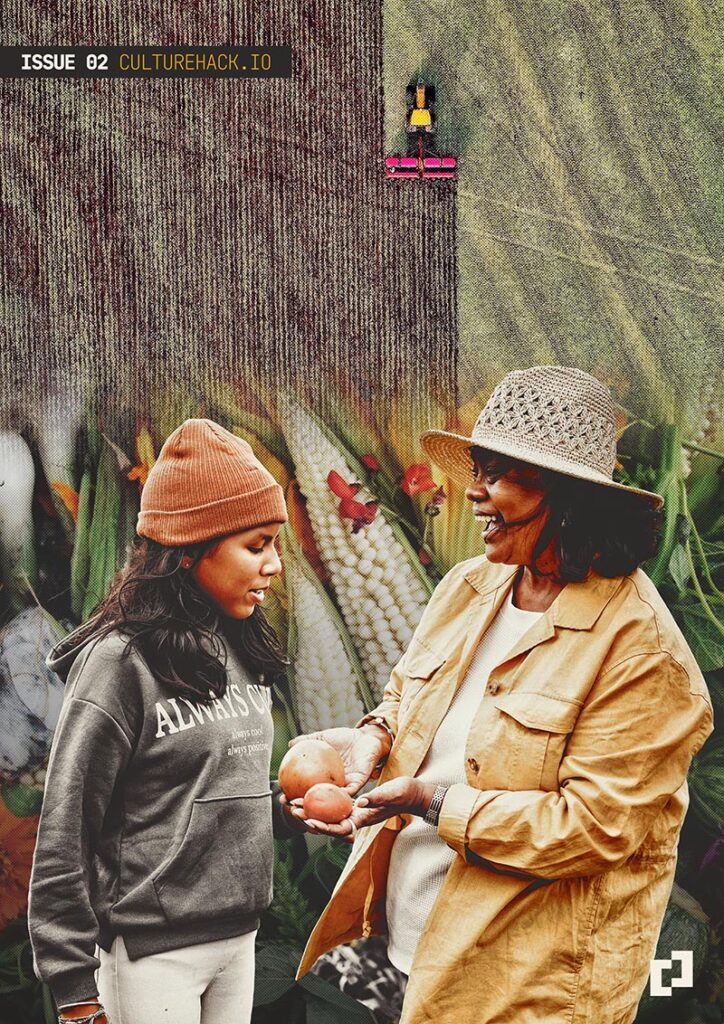

One obvious “solution” is to try to conserve natural systems by empowering indigenous peoples and local communities. Indigenous communities have mastered the art, or at least many have not lost it, of living symbiotically with nature and learning from those experiences. In general, people that live in close relationship with nature, such as place-based farmers and small businesses, have proven to be better stewards of natural land because of their deeper entanglements with the land that they inhabit. Nature Sustainability journal recently mapped the amount of Indigenously owned and managed land throughout the world, finding that it extends over 38 million square kilometers, a quarter of all land outside of Antarctica. The majority (65%) of these lands are still not developed. This study also highlights the great contribution Indigenous peoples are making to conservation despite centuries of colonization, displacement, and oppression.

Indigenous communities have mastered the art, or at least many have not lost it, of living symbiotically with nature and learning from those experiences. In general, people that live in close relationship with nature, such as place-based farmers and small businesses, have proven to be better stewards of natural land because of their deeper entanglements with the land that they inhabit.

Ironically indigenous communities are often fetishized by the same organizations that are sustaining existing neo-colonial power relations and disconnection. There is even a large push to more starkly segregate nature and culture from each other. The “half earth movement,” a call to conserve half of the planet for nature, is often linked to the techno fantasies of ecomodernists, who believe that it is possible to successfully decouple resource use and growth through innovative technologies and endless cycling of resources ( a limited interpretation of a “circular economy”). Proponents of “green growth” argue that the answer to ecological collapse is to invest in efficient technology and introduce the right market incentives so that our economy can continue to grow while simultaneously reducing its impact on the natural world.

Green Growth and Natural Capital

In tandem with the emergence of so-called Green Growth, the past twenty years has elevated “market-based approaches” to nature conservation as the preferred, default framework. Its advocates point out that nature is under continual threat from deforestation, pollution, overexploitation and degradation. Chiefly because economic thinking sees damage to nature as external to “the economy.” This line of thinking – seeing nature as an “externality” — gave rise to the “natural capital” approach, which seeks to assign value to nature. In order for the “services” they provide to be treated as assets and financialized (valued and traded through financial instruments). And as a way to manage risks and dependencies of communities and businesses and articulating the value of nature and its services; whether it be economic, social, environmental, cultural or spiritual value, and whether this value is expressed in qualitative, quantitative or monetary terms. By subjecting nature to mainstream economic valuation and accounting, it supposedly becomes possible for policy makers and businesses to assess the “true” economic costs of natural destruction, the economic benefits of conservation, and even the affirmative business case for investing in conservation and restoration.

The problem with this approach is that it is deeply simplistic and naïve. It does not reckon with the built-in imperative of capitalism to extract and commodify natural resources. It also overlooks capitalism’s inability to look past short-term economic interests and the unfair socializing of business costs (onto the state, communities, and future generations) and the privatization of benefits (profit, return on investment) that accrue through exploiting living systems as “natural resources.” For a natural capital approach to work on its own theoretical terms, it would be necessary to privatize the costs and socialize the benefits. But this obviously would reduce business profits and possibly jeopardize the financial sustainability of enterprises.

For a natural capital approach to work on its own theoretical terms, it would be necessary to privatize the costs and socialize the benefits. But this obviously would reduce business profits and possibly jeopardize the financial sustainability of enterprises.

Predictably, this mode of conservation has not had the desired effect over the past decade. Ironically, the years 2010 to 2020, officially the United Nations Decade of Biodiversity, saw biodiversity declining at accelerating speeds, contributing to what most conservation scientists agree is the sixth mass extinction in the history of the Earth. This anthropogenic extinction has made it clear that global economic growth is incompatible with effective nature conservation. Natural resource management via market incentives and technocratic control – the dominant approach favored by investors, corporations, and states – is worsening our socio-ecological crises.

The conservation funding gap

Many argue that the difficulties in “managing nature” and conserving it stems from a lack of funding. Many policy reports speak of the funding gap with regards to nature and so-called nature based solutions. One attempt to remedy this is to try to treat the “externalities” of nature as capital. A recent report Dasgupta Review The economics of biodiversity, commissioned by the British government, refers to nature “as our most important asset like machines or labor.” According to that same report, “natural capital per person has decreased by almost 40 percent between 1992 and 2014.” It also concluded that it now takes about 1.6 earths to maintain current living standards – which suggests the extent of the depletion of “natural capital.”

Even though a report like this provides useful information with the best intentions, its framework of analysis is flawed. It does not acknowledge that the value of dynamic living systems eludes quantification and monetization, and that by trying to financialize this value and incorporate it into existing market systems, it commodifies nature and invites further market enclosure: the very problem that the “natural capital” approach aspires to fix. Unfortunately, we cannot rely on accountants to save the planet’s natural world because their perspective cannot comprehend the idea of inalienable or intrinsic value – forms of intangible, nonmarket value that are produced in commons. There is a whole register of value in natural, living systems that their calculations cannot express or represent and they have even been trained to discount it. This value-creation exists in different, living circuits of value, outside of the seductive certainties of finance and property rights. The lens of quantification and monetization fails to represent the actual, living dynamics of natural systems, and so misconstrues value as a market price.

Convivial conservation

At the same time, a radical new vision and movement for post growth conservation is emerging and gaining traction. Inspired by conservation practices, Professors Bram Büscher and Robert Fletcher from Wageningen University have developed an alternative approach to conservation policy – “convivial conservation” – that seeks to move beyond strategies of economic valuation and protected areas for land. In their masterly history of conservation movements, The Conservation Revolution: Radical Ideas for Saving Nature beyond the Anthropocene, Büscher and Fletcher describe how capitalist finance and politics have undermined the avowed goals of land conservation and failed to implement effective plans. Their envisioned conservation movement seeks to bring the human and nonhuman world into a more constructive, “convivial” form of everyday engagement, without the imperatives of capitalist finance or assumptions that humanity and nature are separate.

They wish to develop new types of non-extractive but productive land use and finance, facilitated in some cases by a proposed “Conservation Basic Income.” The ideas behind convivial conservation are highly compatible with the vision of commoning set forth by David Bollier and Silke Helfrich in their book Free, Fair and Alive (2019). They posit commons as self-organizing social systems that have a different operational logic and ethos than that of capital-driven markets and the state, which are nonetheless highly generative and value-creating. The point of both convivial conservation and commons is to escape the extractivist imperatives of capitalism and the ineffectuality and corruption of state management of land.

The point of both convivial conservation and commons is to escape the extractivist imperatives of capitalism and the ineffectuality and corruption of state management of land

An important tool in moving these visions forward is what might be called “relationalized finance,” or “commons-based finance,” in which people whose livelihoods and cultures are collectively entangled with land usage, control the financing of their own land. The point is to make it possible to finance nature conservation and restoration without allowing land to be commodified.

What could commons-based finance for land look like? Economic historian Karl Polanyi referred to land (along with money and labor) as a “fictitious commodity,” because land is not actually produced for sale. It is a gift from nature. The treatment of land as private property is an artifact of modern, western culture. According to Polanyi, land, labor and monetary policy should not be subjected to unregulated ‘free markets’ because it results in treating people and ecosystems as objects – commodities – subject to the whims of markets. As living entities, they have their own intrinsic, implacable needs, and failing to acknowledge this simply engenders strife and complexity; it certainly does not support the natural dynamics and needs of living systems as generative circuits of value.

Commons value creating social systems

Now, in the 21st century, it is becoming increasingly obvious that neither the state nor the market are capable of stewarding land for future generations. Short-term interests—the next election and quarterly profit reports—generally prevail among political officials and businesses at the expense of responsible, long-term land stewardship. Future generations have no voice in political and economic decision making because they cannot vote, donate, or otherwise be heard.

When financing land, there is much to learn about what and how to finance. Currently, financing for land tends to promote extractive, market-driven uses. The institutional logic of property rights, markets, and finance makes it difficult for people to think and act outside of the profit and loss systems. Finance capitalism, privileges private financial gain over meeting public needs, other types of finance are feasible and could be implemented. Community land trusts, community supported agriculture, and a conservation basic income are a few of the models for aligning finance with true ecological sustainability. But these systems are possible only if people have meaningful relationships with place—a sense of belonging to the land—and systems of law and culture to support these goals. Private ownership is not the only way to achieve secure land tenure and meaningful connections between land and community. In diverse geographical and cultural contexts, commons-creating social systems can open up new possibilities of eco-friendly land stewardship. It becomes possible to free land from conventional financial and market pressures, bring different types of people into shared purpose around convivial conservation, and strengthen the personal and political will for deeper change.

We can learn much from nature itself from how we can collaborate and organize. We can use Nature’s design principles as a basis and ecology itself gives a blueprint. Healthy ecosystems can thrive in abundance and, within the system, human and the non-human actors can thrive in mutual symbiosis. Various ecologically minded commentators like Jeremy Lent, John Fullerton and Deborah Frieze have written about learning from Nature’s intelligence in building organizations and finance. It is possible to bypass the global economic system and its dedication to wealth accumulation, to create instead new life-enhancing structures. In order to do this, however, we must learn to mirror ecosystem dynamics in our internal and external practices rather than replicate capitalist priorities of private extraction, monetization of nature, and accumulation. In functioning, resilient ecosystems, for example, the contribution of each party creates a whole that is greater than its parts, so long as the sun keeps shining.

We can learn much from nature itself from how we can collaborate and organize. We can use Nature’s design principles as a basis and ecology itself gives a blueprint. Healthy ecosystems can thrive in abundance and, within the system, human and the non-human actors can thrive in mutual symbiosis.

By emulating nature not just in the way we treat the land but in the way it is financed, we are able to create generative, decentralized infrastructures that can make it possible to build commons that care for the land. It helps if we can recognize that complexity science principles apply when dealing with land issues and developing new types of eco-minded land use. Govert Geldof, a Dutch complexity scientist, shows that when dealing with complexity we tend to want to come up with complicated generic models and top-down solutions driven by rules and regulations. But in real life, especially in crisis situations, tidy, rule-driven models are often not very useful in dealing with dynamic complexity. Geldof’s research showed that when we are faced with complexity, the most effective way forward is to look to the practices of people in a specific local domain. There is no other way. He calls this the difference between integrated and integral working. In the integrated method, it is the participants themselves who determine the terms of “the game” and the outcomes to be sought. In the integral method, spectators and experts — outsiders working as analysts or decision-makers — are the ones calling the shots.

Commoning is based on peer governance and therefore by definition, an integrated way of managing and conserving land. This helps explain why commoning can help sow seeds of abundance and create an ecological perspective; communities that care for nature and live in reciprocal relationship with it, are capable of seeing and honoring living circuits of generative value. This unfortunately has all been but forgotten in the mainstream of Western societies. Lucky for us moderns, we do not have to start from scratch in recovering powerful “old ways.” We can learn from existing commons and indigenous people and their practices of land conservation. In any scheme of conservation finance, local and indigenous perspectives and relationships with land are crucial. We can only truly move towards new territories of transition if we are willing to fully acknowledge the rights, knowledge systems, and practices of indigenous people. Humans can no longer pretend that “the economy” and civilization are somehow separate and independent of earthly natural systems. Where local communities have long histories with place, they need to be able to enact their care and stewardship, so nature and people can mutually support each other.