Deep Dive: Window of Discourse

The “Window of Discourse” is a descriptive model for understanding how ideas in society change over time and influence politics. It describes the range of political ideas deemed acceptable to the public. Narratives circulating in the public conversation set the boundaries of public and political acceptability around the “written rules” of laws/policies or the “unwritten rules” of culture.

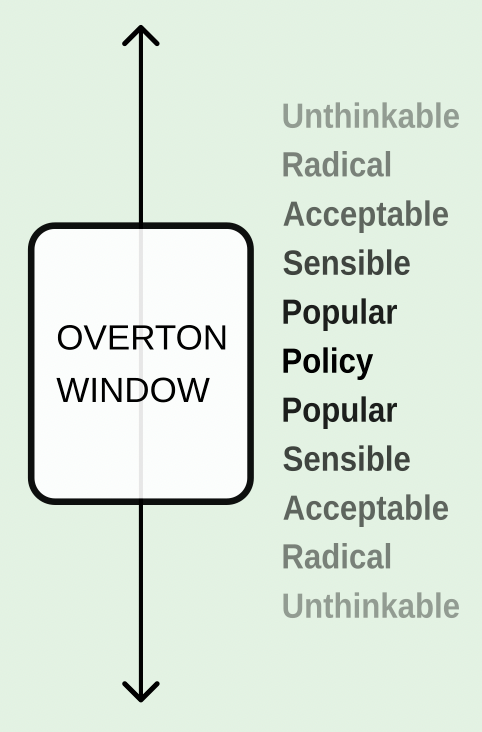

Another term for the Window of Discourse is the Overton Window, developed by Libertarian Joseph Overton in the 1990s to describe the range of policy options a politician could publicly support without seeming extreme. Since then, the concept has evolved beyond policy to include the broader field of culture.

Ideas within the window are accepted as popular, or “common sense.” Ideas on the edge of the window are considered radical, or controversial. Ideas outside the window are unthinkable, thus treated as absurd or threatening. The window is always moving. Social movements can shift what lies inside or outside the window. Over time, ideas that were once unthinkable (think, queer rights, abolition, suffrage or Land Back) can become widely acknowledged, accepted or even institutionalized.

The window’s placement is shaped by power, history, media systems, and dominant epistemologies (ways of knowing), but also by resistance, cultural memory, and imagination. Understanding how it works allows us to examine how some stories or voices are legitimized while others are erased – and how the shape of the public imagination can be expanded.

Case Study: Land Back and the Shifting Window

The Territories of Transition: Land Back to Right Relations offers an example of how the Window of Discourse is actively shifting around Indigenous land and sovereignty.

Until recently, the idea of Land Back—returning stolen lands to Indigenous peoples—was seen as politically impossible and culturally marginal. It sat outside the window of discourse. It was associated with activist militancy or symbolism, but rarely treated as a serious proposal. In dominant/mainstream narratives around the environment, land was framed primarily as a resource, and Indigenous knowledge was excluded from legitimate climate policy conversations.

However, as our research shows, this is changing. Land Back is no longer a fringe idea. In many communities, it is being recoded through stories of healing, youth mental health, cultural revival, and climate resilience. Land is not simply territory – it is memory, kin, and teacher. These stories are helping to reposition Land Back within the realm of legitimate discourse.

The table below gives examples of Land Back narratives for multiple positions across the Window of Discourse:

| Window’s location | Land Back narrative example |

|---|---|

| Policy/Law: What is legally recognized and enforceable | Land rematriation agreements, Indigenous co-management of parklands |

| Mainstream/popular: What’s widely accepted in dominant environmental or justice narratives | “Include Indigenous voices in climate solutions” |

| Sensible/ Legitimate/acceptable: what’s viewed as reasonable or within debate | “Land Back is a necessary part of environmental justice” |

| Radical/Visionary: what’s seen as morally compelling but politically ambitious | “Land Back as the basis for cultural healing and decolonization” |

| Unthinkable/Taboo: what’s considered absurd, dismissed or actively suppressed | “Abolish private property—return all land to Indigenous care” |

Further reading:

Beautiful Trouble – Use your radical fringe to shift the Overton Window.

Earthbound, 2019 – How Extinction Rebellion shifted the Overton window

New Statesman, 2021 – How the alt-right shifted the Overton window