Cities as Territories of Transition

Is it possible to remain hopeful amidst the devastation wreaked by climate change? The authors delve into this question with a focus on cities and their capacity to be territories of transition in the midst of global multicrises and the resultant wave of climate fatalism.

In the face of the climate crisis, hope is waning: worsening IPCC predictions, devastating annual wildfires in the Amazon, constant murders of land defenders — especially from the Global South — and failed climate negotiations. With increasing anxiety and dread, it is not surprising that there is a growing wave of “climate fatalism” making people believe that the world has already lost the battle against climate change. Climate fatalism, however, is just the evolution of the climate-denialist narrative created by the fossil fuel industry, which has historically sabotaged climate consciousness and policy. This narrative is also a form of what Mark Fisher called “capitalist realism,” or our collective tendency to imagine the end of the world instead of the end of the system that is driving its destruction.

For the five of us, women and diverse Mexican youth from the cities, the bonds with the land we inhabit are systematically denied. Yet, living in the contradictions of progress and environmental degradation, we understand that the only way to transform the place we live in is to recover our connection with the territories we inhabit. Ultimately, we can do so by sowing climate hope in urban regions and establishing the importance of our connection with land for our bodies, our ancestors, other living beings, and the cosmos.

For organizers and defenders, however, hope remains. Not in the false climate solutions, based on infinite economic growth and technology, but in the climate justice and territorial defense movements that are showing us different narratives to reimagine the future. As well as different ways of inhabiting our territories in communion with community and nature.

The concept of territory, which comes from the resistances of Indigenous and Afrodescendant peoples and peasants, vindicates a term that hegemonically has been associated with the sovereignty of the nation-state. The territory, from a counter-hegemonic narrative, goes beyond the state into spaces we inhabit, appropriate, and occupy. Spaces that are not binary like those conceived in western modernity, but simultaneously symbolic and material; natural and social; sensorial and rational; external and internal. These territories are formed through a process of territorialization, in which identities, and most importantly, territorialities which are ways of being, feeling and living the territory are created.

The territory, from a counter-hegemonic narrative, goes beyond the state into spaces we inhabit, appropriate, and occupy. Spaces that are not binary like those conceived in western modernity, but simultaneously symbolic and material; natural and social; sensorial and rational; external and internal.

Normally, we do not associate territories with cities. However, cities are actual territories with all their complexities, although not always in the “counter-hegemonic” way. On the contrary, the model of the “global” or “cosmopolitan” that is presented as the peak of progress and development coming from the Global North and through which many global cities are being gentrified, is part of a dominant territoriality that responds to capitalist modernity.

Although cities are complex networks of relationships between people, land, critters, space, and even time, currently, most of them are planned and managed as unitary places structured over anthropocentric, racist, patriarchal and classist structures that perpetuate social disparities, the destruction of the Earth, the creation of sacrifice zones, the extractivism of many territories and bodies, the centralization of power, and the hoarding of resources.

Instead of harnessing the energy of their diversity and the contradictions through communal methods that allow us to overcome the climate crisis, urban planning often operates under a logic of environmental and communitarian disconnection. Many people who live in major cities have given up on doing anything to address the climate crisis, because on top of dominant narratives, the spatial structures we experience in cities are intrinsically unequal, individualist, isolating and harming.

While millions of people are already experiencing the worst effects of climate change — being displaced or killed by climate disasters, for example — central urbanities live in some parody of “The Matrix,” enjoying all the benefits of “development” at the expense of the suffering of their peripheries and in general the sacrifice zones of the system. For example, those of us who live in central areas of Mexico City have been told that the ecological breakdown is something we will experience in 10 or 20 years mainly due to the lack of water. However, our current extractive lifestyle has already driven the collapse of the peripheries and other areas of the country, from where we drain the water we consume, and who are experiencing lack of water due to this and the climate crisis.

In sum, cities, as we know them in the capitalist world, are unfair and unsustainable. Yet, in the Global South, and specifically in Latin America, most people live in urban areas. This is primarily because urban immigration has represented the only survival mechanism for a lot of historically oppressed people. Many of our ancestors moved from rural areas and regions or their territories to major cities in hope of a better life. However, in times of climate crisis, our hope is to save these spaces from the corrupted state they have evolved into.

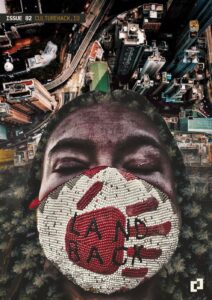

As communitarian feminists have expressed, territorialization does not only concern the land, but it also directly concerns our bodies. Our first territory is our body (not separated from our mind), which is constantly feeling, and in many cases, confronting the oppressive and exploitative logic we live in. In the case of “urban people,” our body-territories are “body-cities” with all its territorial implications. The first frontier in which we feel the system, the extractive colonial city model we live in, are our skins — our City Skin/Urban Dermis. We use that metaphor to express that we are always touched by power dynamics (like Michel Foucault has defined in his concept of micropower). In response, we can feel their varied violence, discomfort, and trauma or, in some cases, all the contrary: agreement and comfort.

Our first territory is our body (not separated from our mind), which is constantly feeling, and in many cases, confronting the oppressive and exploitative logic we live in.

In the exercise of resistance against the climate crisis and the current violent system that caused it, it is crucial to recognize the sensations we feel from our position inside those power relations. As young people from Global South cities, we have somehow benefited from the extractive system (in a broader way than many other territories), but at the same time, cities are not homogenous, and we are not the “hegemonic subject” (white, bourgeois, heterosexual, etc). Neither are we the “most affected” subjects by this system and by the climate crisis. As most people, we are at the same time oppressors and oppressed. We live in a constant state of contradiction between hegemony and resistance, in between what already exists and what we want to bring and create.

The tough contact with power dynamics allows us to see that our bodily experiences are territorial ones because the rage, fear, anxiety, and discomfort that contradictions make us feel can either paralyze us or mobilize us for system change. We cannot deny that we are constantly “seduced” by power. From it we receive many comforts and feeling them from a conscious vision can help us recognize our “privileges” and put them in a place of constant personal and collective reflection and work.

The acceptance and vindication of those bodily experiences, which are also material realities, can lead us to start the reoccupation and transformation of urban territories. Our way of resisting the power dynamics we are touched by, our way to reclaim the agency within our bodies and urban territories — between our skins and the city. Reclaiming our agency means accepting that we, as the urban youth, can also help bring back the ties between oneself, the community and the land; we can restore the memory and value of the places that we are inhabiting, and in that process, sow climate hope.

Our way of resisting the power dynamics we are touched by, our way to reclaim the agency within our bodies and urban territories — between our skins and the city.

As part of the youth climate movement, we understand that climate hope in the cities is necessary to outnumber the narratives of desolation and annihilation that are stalling climate action. We are touched by power and contradictions in our daily life. Still, we can also be touched by climate hope. We can participate in urban projects to reconquer spaces for nature and community, like trueque, tequio, urban gardens, time banks, fair markets, the recuperation of commons, assemblies, etc.

Recently, through our youth collective (Legaia), we implemented a project called “Sowing Climate Hope” in Popotla neighborhood in Mexico City. This is a place with a lot of history. Before the colonization, Popotla was part of the city of Tenochtitlan, but administratively it was part of the kingdom of “Tlacopan”. Here, we can find the oldest avenue in America (Calzada México Tacuba), or the “Árbol de la Noche Victoriosa” (Victorious Night Tree) where Hernán Cortés cried after he was defeated in a battle by the Aztec resistance against colonization.

The streets of Popotla have seen the different changes of territorialities in Mexico City. Currently, it is almost completely gentrified. Apart from inhabiting it, we think it is a very symbolic place for change, resistance and culture hacking. That is why we decided to “sow climate hope” there.

The name of the project returns to identifying that in cities there are many people like us that are worried by the climate emergency but often fall into climate fatalism because their political imaginations are colonized by the dominant narratives, and their daily experiences are in hegemonic territorialities. In this context, we decided to “sow climate hope” by literally prompting people to sow in an urban garden, and through that process, creating communitarian ties, restoring the link with earth, recovering the biocentric territoriality that once was in Popotla and advancing towards climate justice.

For that purpose, we allied with a local cultural center (managed by the local government). We received a workshop on urban gardens, and we also had the opportunity to give a talk on sowing climate hope and invite people from other communitarian processes around the city to talk to the Popotla neighbors about topics like indigenous resistances in cities, herbalism, or the potential of urban gardens. Through the process of territorializing our narratives, of “acuerpar” (embodying) our discourses, we learnt a lot of lessons.

Transitioning towards biocentric and communitarian territorialities in cities is very tough and is not linear. There will always be contradictions and disputes between the life-centered narratives we seek to promote and the hegemonic narratives that try to end with the political imagination. There were people who tried to discourage us by telling us that, no matter what we did, the world would never change because it has always been like that.

Also, in a very “innocent” activity like pasting posters with different slogans around our campaign, we realized that whenever there are attempts to promote new narratives, power will try to hinder them. Most of our posters were torn off by the “authorities,” since in Mexico City it is “illegal” to paste them. The white-western-modern obsession with “sanitation” and “order” is expressed in such policing. So is the capitalist logic of urbanization, since only commercial or official government posters are “allowed.” Political messages like ours are just turned off, showing us how the hegemonic territorialization of the state tries to control communitarian ties.

Despite this, we realized that territorializing life-centric narratives, as uncomfortable it may be, is more than necessary. Some people we knew showed us we are not alone in our feelings, or in our bodily experiences. They opened up, telling us how environmental detachment affected them or expressing to the group how they feel a “colonial wound” due to the cultural detachment from their indigenous roots. They showed us how we are not alone in feeling touched and seduced by power or in feeling discomfort from our comforts.

The most important is that we verified what we say in this text. Contradictions can mobilize us for system change, but we must always strive for clear collective and political objectives. We must acknowledge that rethinking the city as a place of resistance — and co-creating cities that are part of the solution rather than the problem — requires the rejection of capitalist top-down management of space. This demands a deep confrontation within our own “city-bodies” or “urban dermis”, and within society to be able to dismantle western rationality and all oppressive systems.

Contradictions can mobilize us for system change, but we must always strive for clear collective and political objectives. We must acknowledge that rethinking the city as a place of resistance

Embracing our contradictions, feeling them, using them as an engine to our resistance, building community, recovering spaces for nature in urban areas, solidarity, and the interrelations with our territories are the solutions to transform cities into life-centered alternatives to all the identities and beings that inhabit them. Solutions to start a process of transition, reorganization and transformation from the individualist, violent and hetero-patriarchal dominant territoriality to biocentric and communitarian ones.

Let’s vindicate our territories!

References

- BBC News Mundo. (2022, 12 junio). Por qué se están viralizando los “fatalistas” del clima y quién los está combatiendo. https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-61569009

- Asamblea Ecologistas Popular [@AsambleaEpop]. (17 de enero 2022). La creencia de que ya no hay alternativa al sistema actual se esconde bajo el nombre ‘’realismo’’, y es, actualmente, la forma predominante de propaganda capitalista-racista-patriarcal [Tuit]. Recuperado de Asamblea Ecologista Popular en Twitter: “La creencia de que ya no hay alternativa al sistema actual se esconde bajo el nombre ‘’realismo’’, y es, actualmente, la forma predominante de propaganda capitalista-racista-patriarcal. Abrimos hilo sobre la relación entre el realismo capitalista y el pesimismo climático” / Twitter

- Betancourt, s. (2017). “COLONIALIDAD TERRITORIAL Y CONFLICTIVIDAD EN ABYA YALA/ AMÉRICA LATINA”, Ecología Política Latinoamericana: pensamiento crítico, diferencia latinoamericana y rearticulación epistémica, Vol. 1, Buenos Aires, Argentina, CLACSO, 2017, p. 216.

- Rodríguez, Jorge, et al., 2011, “Población, territorio y desarrollo sostenible.” Santiago de Chile: CELADE-CEPAL.

- Cuberes, David, 2020, “El origen y crecimiento de las ciudades.” Panorama social 32: 9-21.

- Gunder Frank, André, 1967, “El desarrollo del subdesarrollo”, en revista Pensamiento crítico, La Habana, Cuba. Disponible en: http://www.filosofia.org/rev/pch/1967/pdf/n07p159.pdf

Footnotes

- BBC News Mundo. (2022, 12 junio). Por qué se están viralizando los “fatalistas” del clima y quién los está combatiendo.

- Asamblea Ecologistas Popular [@AsambleaEpop]. (17 de enero 2022). La creencia de que ya no hay alternativa al sistema actual se esconde bajo el nombre ‘’realismo’’, y es, actualmente, la forma predominante de propaganda capitalista-racista-patriarcal [Tuit]. Recuperado de Asamblea Ecologista Popular en Twitter: “La creencia de que ya no hay alternativa al sistema actual se esconde bajo el nombre ‘’realismo’’, y es, actualmente, la forma predominante de propaganda capitalista-racista-patriarcal. Abrimos hilo sobre la relación entre el realismo capitalista y el pesimismo climático” / Twitter

- Betancourt, s. (2017). “COLONIALIDAD TERRITORIAL Y CONFLICTIVIDAD EN ABYA YALA/ AMÉRICA LATINA”, Ecología Política Latinoamericana: pensamiento crítico, diferencia latinoamericana y rearticulación epistémica, Vol. 1, Buenos Aires, Argentina, CLACSO, 2017, p. 216.

- Rodríguez, Jorge, et al., 2011, “Población, territorio y desarrollo sostenible.” Santiago de Chile: CELADE-CEPAL.

- López, Eugenia. 26 de junio de 2018. “Lorena Cabnal: Sanar y defender el territorio-cuerpo-tierra”. Avispa Midia.