Narrative analysis

“We are liberating the land,

building up the village.

Our generation is returning back to the land.

My heart pulls me back to my territory.

This is healing.”

—ToT participant

In May 2023, Culture Hack Labs convened a group of leading BIPOC and Indigenous activists to form a community-of-practice in relation to “the Territories of Transition” (ToT) framework. The framework was developed through research led by Culture Hack Labs in 2022, which identified three areas of intervention to change humans’ relationship with land and nature:

- Decolonization

- Interdependence

- Radical Relationality.

Building upon this research, the community-of-practice (the ToT group) identified three additional areas of inquiry:

1: Land, youth and spirituality

The ToT group was interested in understanding whether and how young people engaged in activities aimed at defending the land maintain a spiritual practice?

2: Indigenous in non-Indigenous narrative spaces

Accepting that cultural transformation is ongoing and somewhat inevitable, the ToT group is interested in understanding whether it is possible for non-Indigenous people to adopt and embrace Indigenous knowledge and practices (medicine, science, rituals, etc.) without holding the same connection to the land as Indigenous people.

3: Resistance collectives

Land, in particular Indigenous land, has been the object of violence: extractivism, exploitation, land loss and displacement. Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups have resisted and attempted to protect the land and culture, often finding within the territory (territories of transition) a place to explore new ways of living and being. New paradigms. In this last area of inquiry, the ToT group was interested in finding examples of transformative spaces and strategies that could maintain and restore relationships with the land(s) and communities. Places of connection, reconciliation, places of healing and reparation.

Through this additional research, the goal was to discover narratives around land that could connect (self-defined) Indigenous communities with non-Indigenous communities. Indeed, it is within these shared narratives that lies the potential to transform culture and society. At Culture Hack Labs, we believe that research is not relevant if not guided by those who are leading (and living) social change. This additional inquiry was therefore an opportunity for the ToT community-of-practice to orient Culture Hack Labs’ research to effectively address the current challenges that pertain to the defense of the land.

The research provided key insights, which essentially present potential narrative connectors between narratives spaces explicitly led by Indigenous people and narrative spaces led by people that do not necessarily identify as Indigenous:

- There is a growing recognition of the need to relate to the land in new ways among non-Indigenous and Indigenous communities. While Indigenous people’ relationship with the land has always been rich and multiple, encompassing spirituality, wellbeing and sovereignty, today climate change seems to be pushing non-Indigenous people to reflect about their own relationship to the land – one that moves beyond anthropocentrism. However much remains to be done, as Indigenous sovereignty is too often left unrecognized in mainstream conversations about land. For instance, non-Indigenous people who embrace Indigenous spiritual practices too often also fail to acknowledge that for spiritual practices to exist, the land and Indigenous sovereignty must be defended.

- We found that healing and mental health are key narrative connectors. Both non-Indigenous and Indigenous spaces are concerned by mental health issues, exacerbated by climate change (eco-anxiety), but also by the loss of one’s culture – this is most relevant in Indigenous groups, but also in immigrant communities. The idea of healing is thus prevalent across the board – more so than spirituality. For Indigenous youth, healing is deeply connected to being able to reclaim and access their land, where culture is situated. This entanglement is less obvious for non-Indigenous communities.

- As many have lost a direct connection to the land, the notions of “ancestors” or “ancestral knowledge” have become a substitute for land. What connects people to their land is the ancestral knowledge that originally came from that land. This is particularly true for diasporas and immigrant communities. We thus generally see non-Indigenous people connecting more readily to ancestral knowledge than to the land. However, for Indigenous communities, Indigenous knowledge is ancestral knowledge. We therefore see another narrative connector here.

- Cross movement solidarity is increasing, and land has become central to most movements. Growing movements like Land Back, Food Sovereignty, Agroecology, or environmental movements seeking to stop extractive industries show that land has become the place of social transformation. In addition, historically marginalized communities see the land as the place of reparation, decolonization and reconciliation. In social movements, land is a narrative connector. Importantly, cross-movement solidarity is happening across the globe, across social causes (workers rights, LGBTQIA+ rights, Black Lives Matter, women’s rights, Indigenous rights…). More and more activists are calling for the creation of a movement of movements.

These narrative connectors can orient future narrative interventions. You can find here an extensive analysis of the intersections between narrative spaces – or narrative connectors. In addition, our previous research provides guidance as to how to direct narrative interventions. Below we review its key findings.

Narrative Mapping

Key to CHL’s hack methodology is the identification and mapping of narrative communities. In our initial research, we mapped 7 narrative communities based on their underlying belief systems on land. These communities represent the most important perspectives and the most currently active conversations at the time of our research. However, we highlighted them because they represent archetypal narrative forms ie. their core logics and ideas are those pervading the narrative space at the moment.

| Narrative Community | Description of core logics/ ideas & main actors | |

| 1 | Community Land Trusts | CLTs are models of collective ownership of the land to ensure affordable housing and address socio-economic inequalities in large cities. The idea here is to offer an alternative to individually-based and market-driven ownership of the land, which generates a lot of exclusion. The conversation around CLTs is led mostly by local communities – including a growing youth-led movement. It has a low impact on the mainstream conversation around land at the global level. It is stronger at the local level (especially in context of local governmental policies). |

| 2 | Land Back | A movement led by First Nations in North America reclaiming land that was taken from them during colonization as a form of reparation. By reclaiming the land, the goal is also to protect nature, biocultural diversity, Indigenous traditional knowledge and spiritual practices. The idea here is that Indigenous Stewardship of the land is how we ensure humans and ecosystems are safe. This community has reached the mainstream, including holding a strong social media presence and influencing pop culture. |

| 3 | Rights of Nature | A growing legal movement and conversation that seeks to grant nature legal personality to allow it to “defend itself” through the legal system. The idea here is that nature can also have sovereign rights and (legal) agency like humans. A community mostly led by lawyers, NGOs, activists. It is a small community within the mainstream conversation – although Ecuador, which has recognized the rights of nature in its constitution, has recently often made the news because of its strongest protection of nature, as a result. |

| 4 | Comunalidad | A Oaxaca-based community practicing a decolonial and Indigenous-centered view of the land – one that is based on the collective, that applies a spiritual lens to the land. It also tries to change the language used to describe land (property, rights, etc) and that we inherited from modern Western culture. The idea here is that Indigenous cosmovision and stewardship is a lived praxis. It is real, it can happen and not be a mere theory. It is a small, but growing conversation in Mexico. It has joined the likes of other collective initiatives (Rojava in Kurdistan, …) that seeks to implement new paradigms. |

| 5 | Food sovereignty | Movement that sees as fundamental the right to control, decide and manage the means of producing the food we consume. La Via Campesina, the international farmers’ movement has made this concept more widely known and popular. Food sovereignty is tied to land sovereignty: when we own our land, we can own the way we produce food, and we stop relying on external market forces. The core idea is Sovereignty. Sovereignty of Land and Food systems is how we protect/defend life. This conversation is mainly led by experts, NGOs, local farmers, Indigenous people, etc. While popular in the social justice world, this concept is still a small conversation in the mainstream. |

| 6 | Ecocide | A concept that originated in the 1970s and became part of the environmental movement that has sought to create a legal crime to punish those who destroy nature. By creating a crime of ecocide, the core idea is that nature is life, land is Life. Should you “kill” it, you commit a crime.A growing community in the Global South – we see it often mentioned by movements calling out extractivist megaprojects. The conversation is mostly local or regional. |

| 7 | Bioregionalism | An emerging and regionally-focused narrative community that proposes an alternative to environmentalists’ view of preserving the environment (national parks, reserves, etc.) In lieu of the nation-state and its human-made borders, land is defined according to ecosystems (mountains, riverbeds, etc). People are also grouped according to their attachment to the same ecosystems instead of nationality or ethnicity. The core idea is that the territory defines us (living species), that we are the territory. Thus new forms of collective care of the land can emerge. The community is mainly led by policy makers, NGOs, activists, Indigenous people. It is still a small community within the mainstream conversation. |

For a deeper look at how the listed narrative communities relate to the three areas of inquiry, see our report Territories of Transition 2 – August 2023.

Another important part of CHL’s methodology is assessing narrative communities potential for evolution: can this narrative community make us evolve as a collective? In mapping and assessing, we focus on the archetypal behavior of the narrative community: its core ideas and logics. We are thus able to trace the key current patterns or dimensions of the narrative space: what are the core logics that are prevailing at the moment, and where are we moving towards?

After reviewing the narrative communities in light of the additional research, we are able to identify the following key dimensions/patterns of the narrative space:

- Private Property : The dominant understanding of land is that of land ownership – rooted in the enclosure of land and territory, a belief system that is at the heart of colonial, industrial and neoliberal systems of domination. This is the status quo, where we ought to move away from. Narrative Communities like Community Land Trusts, Food Sovereignty and somehow still carry elements of this logic by focusing on “ownership”: who owns the land and how.

- Land Back: Indigenous people see the land as a sentient, having agency, an active partner who shares knowledge. This pattern is justice oriented and follows a decolonial thought. Narrative Communities that fall within this pattern are seeking justice, equity, sovereignty and reparations through the return of the land. They are bringing attention to centuries of injustice and a history marked by genocide, illegal land grabs and displacement. Land Back is the most illustrative narrative community. However, Ecocide, Rights of Nature, CLTs and Food Sovereignty also hold a justice dimension. What our latest research shows is that these movements are anchoring land as the place of social transformation. They also understand healing as the next step after justice is obtained.

- Back to Land: Narrative communities following this dimension are seeking new ontological and epistemological models for relating to land, often these propose policy, advocacy and economic models that express deep relationality and care for all life. Comunalidad or Bioregionalism are situated there. This is also where we locate the mental health conversation, the desire for belonging, ancestral knowledge and spirituality, and addressing the need to revisit our relationship with the land.

We use a map to depict the narrative space, its patterns and where narrative communities are situated. In the mapping below, the bottom left quadrant represents the part of the narrative space that still holds dominant understandings of land ownership (Private Property). However, through our research, we found that a growing number of narrative communities are moving into the Land Back dimension. They hold the highest potential for change to move towards the Back to Land dimension where few communities are at the moment.

To further understand the potential for change here, we can introduce three concepts – Narrative Vectors, Overton Window and the Onto-shift.

Narrative vectors are potential pathways for evolution within the narrative space.

In the above mapping we can identify two narrative vectors that have the power and potential to shift the narrative space. We can see that for there to be meaningful change within the narrative space, narrative communities within 1) Private Property and 2) Land Back dimensions must move to the top right quadrant of the mapping incorporating deeper understandings of relational ontologies and epistemologies of care. Through this we can define the following narrative vectors:

- Private Property to Land Back: In this vector narrative communities that are rooted in the conceptual domain of enclosure begin to question the underlying, tacit and deep logics that somehow have remained unquestioned. Through this, there is a growing awareness of justice, retribution and reparations.

- Land Back to Land Back to Right Relations: In this vector, narrative communities realize that for a transformation of systems, a transformation of the deep conceptual models of our relationship to land and to the more-than-human world is required. In this phase, communities are experimenting with new narrative models that redefine and transform the boundaries of relationality to land, our bodies and more-than-human life.

These two identified vectors for narrative evolution within the narrative space leads to our reframe strategy, which will be articulated below.

The idea of the “Overton Window”, or “window of discourse” is a descriptive model for understanding how ideas in society change over time and influence politics – and helps us to understand the mapping framework.

Another way to look at these vectors for narrative evolution is to use the concept of the Overton Window. The overton window describes the range of political ideas deemed acceptable to the public. Narratives circulating in the public conversation set the boundaries of public and political acceptability around the “written rules” of laws/policies. While the overton window is about policy choices, we see a broader cultural shift as an end in itself (a change in the “unwritten rules” of culture), not just a means to the end of policy change (Robinson, 2018). We need both.

Our analysis of the narrative space has shown that the following as it relates to the overton window:

- The dominant understanding of land as a resource in service to the conquest of individuals, corporations and political entities still remains the unquestioned belief system within the narrative space. This hegemonic position holds the most power/potential and consequently is at the root of the issues of inequality, ecological destruction This is enacted and expressed through a multitude of laws, policies and cultural modes that have been the warrant for the colonial and neoliberal eras.

- At the fringes of popular discourse we are finding narrative communities that are understanding land as the means in which decolonial actions can be taken, through reclamation, reparation and retribution. Moreover land is at the heart of a justice oriented movement that aims to bring solutions to the problems of the polycrisis.

These two perspectives mark the boundary of the overton window or window of discourse in popular culture. However we recognise that this discourse space still remains wedded to ontological models that perpetuate anthropocentric, capital-centric and Self-Other narrative forms. We want to further shift the overton window by strategically pushing the far edge of what is considered acceptable within a range of policy options – towards the top right hand quadrant (in which power is decentralized and change is transformational), making what was once seen as fringe/radical become common sense.

An ontological shift (“onto-shift”) is a fundamental shift in the very ways we view, understand, sense, relate and engage with the word (Bollier and Helfrich, 2019).

Another way to describe this strategic shift -make the radical common sense and evolve cultural narratives – is the onto-shift. A shift in ontology. The new ontology here is a non-anthropocentric, life-centric way of being: an escape from the onto-political framework of the anthropocentric, extractive and growth oriented modern West in which nature is seen as separate from culture. To truly see a more radical transformation in the narrative space, the underlying logic and values of the discourse needs to be shifted. We identify this shift as moving from the bottom left quadrant to the top right. In the context of the current narrative space, this onto-shift will embrace relational ontologies that transform our relationship with the land, from subject/object towards horizontal relationships where humans and nature are part of the land and vice-versa.

Narrative Objectives

A narrative objective is the strategic direction we want to pursue in the narrative space. This direction is based on the Narrative Research Point of View and the mapping process. It provides the basis for the reframe.

Now that we have established the key narrative vectors and the required transformation in the dominant discourse we can articulate our narrative objectives as follows:

- Bring awareness to the ‘legacy of enclosure’, calling out the perpetrators (past/present) and beneficiaries of this regime of domination, extractivism and exploitation. However, through this, the key narrative strategy will aim to make the connection between unquestioned cultural modes, narratives and belief systems of ‘land ownership’ and the polycrisis.

- In communities that are rooted in decolonial discourse, that are asking for reparations and retribution, we want to bring about greater awareness to the needed ontological transformation in the existing cultural models that define our relationship to land.

- Support and amplify existing initiatives and narrative communities that are experimenting with new and ancient conceptions of land that embrace deep-diversity and deep-relationality ontologies.

In summary we can describe a ‘transition pathway’ that moves through three stations, from land ownership to land back, and from land back to land back to right relations. When we say ‘transition pathway’ we are referring to a pathway of narrative evolution that can act to transition from anthropocentric cultural modes towards beautiful alternatives through ‘deep adaptation’ to the conditions of the polycrisis.

Reframe Strategy

Taking into account the above narrative vectors, overton window and narrative objectives we came to the following reframe strategy.

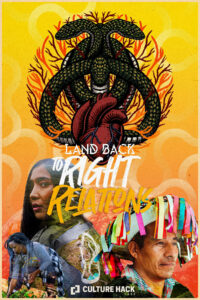

Frame: Land Back to Right Relations

This frame was first found in our initial research within the Land Back movement, and furthers the justice oriented meme of ‘Land Back’ with “Right Relations” indicating the needed ontological shift towards deeper and more radical relationality. This frame not only challenges the dominant understanding of land ownership but also engenders a cognitive dissonance that demands a reappraisal of what ‘right relationship’ means. Although we can by no means generalize Indigenous ontologies to a set of common principles or values we can assert that they all emphasize a more profound relational worldview than incumbent anthropocentric models. It is this deep relationality which is key in providing a “justice + ontoshift” frame and through this providing a way to understand ‘land as a transition pathway” – from justice (land back) to radical relationality (right relations).

The next part of this briefing: “Embodying Indigeneity” provides inspiration for the ontological shift needed alongside demands for decolonisation and reparations among Indigenous movements.

Footnotes

- For the purposes of this report we will use the definition of Indigenous of Aboriginal Academic Tyson Yunkaporta: “an Indigenous person is a member of a community retaining memories of life lived sustainably on a land-base, as part of that land-base. Indigenous Knowledge is any application of those memories as living knowledge to improve present and future circumstances.”

- Culture Hack Labs (2022). Territories of Transition

- Culture Hack Labs (2022). Territories of Transition

- We define Indigenous-led narratives as narratives coming from initiatives that are being led by groups that explicitly self identify as Indigenous. These areas will include non-Indigenous people following explicit Indigenous leadership and direction. We will compare these areas with initiatives that are led by non-Indigenous groups, for example, other social movements or institutions that might seek to include but are not being led by Indigenous people.

- For a longer version of the insights, please see the Research Summary document).

- A narrative space is where a group of narratives coexist and interact with each other within a specific timeframe.

- Culture Hack Labs (2022), Culture and the Anthropocene

- Bollier, D., & Helfrich, S. (2019). Free, fair, and alive: The insurgent power of the commons. New Society Publishers

- https://www.lifeworth.com/deepadaptation.pdf

- Culture Hack Labs (2022). Territories of Transition

- Culture Hack Labs (2022), Culture and the Anthropocene

- Alnoor Ladha and Lynn Murphy (2022), Wealth as Territory of Transition