Embodying Indigeneity

“There is still time to heal humanity and save the Earth. Therefore, we fight for another world to flourish. In the face of the crisis of capitalist civilization – confronted with serious ecological, social, economic, health and political problems –it has never been so urgent to value the resistance of Indigenous peoples and their world views. Values based on relationships of belonging to nature, generosity, non-accumulation of goods, non-commercialisation of life and cultural resistance. We defend an ecology that denounces the unsustainable patterns of production and consumption, dependence on fossil fuels, and financialization as a mechanism for perpetuating inequalities and territorial domination. We criticize private appropriation of land, water, forest resources, biodiversity, genetic heritage and knowledge.”

Sonia Guajajara & Célia Xakribá, We are the Earth. 2022

This section sketches out how Indigenous ways of knowing and being provide inspiration for the ontological shift needed to move beyond the idea of land ownership and its upstream values of separation, extraction, exploitation and enclosure that propel our current capitalist and colonial socio-economic systems.

Context to the term “Indigeneity”: In recent years, the conversation around Indigeneity has surged to the forefront of social and academic discourse. At the heart of these conversations lies a tension between identity and relationality. The concept of ‘Indigenous’ has historically been used as a tool to group together a myriad of peoples, each deeply connected to their specific geographies and stories. While this categorization was conceived as a means of empowerment and recognition, it has often been critiqued for its potential to homogenize and, in doing so, erase the individual narratives and unique histories that define each group. As Trask and LaDuke have argued, while collective identity can serve as a powerful rallying point, it can also overshadow the nuanced differences that each Indigenous culture embodies.

Indigeneity embodies a profound philosophy of relationality, particularly in the context of the land. Indigenous cultures have long fostered a symbiotic relationship with the land, one that transcends the Western concept of ownership in which land is alive, sentient and kin. However, the scars of colonization run deep. The imposition of foreign land ownership paradigms and value systems disrupted the equilibrium that had existed for millennia. For this reason, it is critical to note that embodied indigeneity is not just an ontological or epistemological perspective but most importantly, a political perspective – Indigeneity refers explicitly to the carriers of interconnected value systems that are actively undermined by ongoing colonial capitalist modernity. In response, movements like ‘land back’, represent not just a call for territorial reclamation, but a profound plea to realign with ancient ways of relating and coexisting. In this realignment, taking responsibility for deviation from kinship with the rest of the living world by cultures of separation is key. In order to actually learn from embodied indigeneity, the mode by which that learning is done cannot itself be yet another form of extraction. Such movements emphasize a return to balance, where land isn’t seen as a mere commodity, but a vital partner in the dance of existence.

Before sketching out what embodying Indigeneity looks like, three points are important to set the scene. First, it is pivotal to tread cautiously when discussing Indigeneity, ensuring we avoid the pitfalls of monolithic interpretations. Indigenous populations, while sharing some collective histories and values, exhibit a rich diversity that stands in stark contrast to cultures that have been molded by the forces of individualism (as outlined in the context).

Second, we propose cultivating a more animistic and relational way of relating to the earth should become common sense. The question of non-Indigenous people reframing their relationship to land in ways inspired by Indigenous perspectives is complex and involves considerations of respect, cultural sensitivity, and decolonization.The more than 500 years of ecocide and genocide continue today – the erasure of indigenous peoples is not something of the past. This knowledge must come with a deep commitment and responsibility to defending the land from the unrelenting forces of extractivism and the destruction of cultural and biological diversity.

The ecocidal and genocidal project of colonialism did not end with the ushering in of neoliberalism or late-stage capitalism. This is evidenced by the continuation of land-grabbing, wage slavery and continual assimilation of the planet under capitalist value metrics that play out along settler colonial power asymmetries that place Indigenous ways of life ever more at risk. Approaching this matter with care, understanding, and an acknowledgment of historical context, we propose Indigeneity offers a unique lens through which we can understand the world. This lens helps all of us recognize that we aren’t mere observers or dominators of nature but integral parts of a vast, interconnected tapestry.

Third, as we navigate this terrain, it’s imperative to remember that decolonization is not merely a metaphor. Decolonization is a tangible, active commitment to dismantling oppressive structures and the actual return to land.

Embodying Indigeneity challenges Western paradigms

We build – and are built – on webs that link us to both the future and the past with the same intensity. We are territory, tradition and knowledge. We are the matriarchal force that teaches and welcomes. The land is our essence; the source of life and existence. Who are we? We are the original peoples. We sprout from the ashes of burnt trunks. Even when pruned, we know how to regrow. For five hundred years we have resisted the commodification of life, and those who want to tear our roots from our territory, to fracture our world, our common land.

Sonia Guajajara & Célia Xakribá, We are the Earth. 2022

Embodying Indigeneity challenges dominant narratives that often view humans as separate and superior to nature. “Western” in this document refers to the hegemonic forces of Global North nations that were historically the curators of colonialism and capitalism. Western ontologies promote separation from and exploitation of nature. This stems from Enlightenment theories from Descartes’s separation of mind/body (Cartesian Dualism); to Newton’s metaphor of the world as a mechanical system and the idea of fundamental existence of a positivist, objective world made by discrete ‘things’. To sketch out what a lens of Indigeneity might look like, we draw on Indigenous ontologies as well as Post-Humanist scholarship.

Embodying Indigeneity entails three key elements: First, the earth is alive. Indigenous perspectives tend to be Animistic – a way of relating to the world that attributes “animate” qualities to a range of human and non-human beings, such as the environment, animals, plants, spirits, and forces of nature like the sun, moon, winds or oceans. Nature and culture/society fuse into one another.

A Western iteration of Animism is Gaia theory which popularized the idea of Earth as an animate, living and self-regulating organism. These observations have been “reinforced” by scientific developments shedding light on the “self-organizing/smart” structure of living matter. For example, the symbiotic relationship between the soil, fungi, and plants show how trees/plants communicate through their roots and vast underground networks of mycelium.

Second, the world is inherently interrelated. Indigenous ontologies highlight the importance of interconnectedness, relationality, mutual care, stewardship, and a sense of duty towards all life forms. The self isn’t conceptualized as an insular entity; instead, it’s seen as a nexus within a vast network of relationships—extending to other humans, the natural world, ancestors, and even future generations. Radical relationality has also been explored by Post-Humanists and Eco-Feminists in their critiques of the binary logics of Western paradigms that foster exploitative hierarchies, marginalize Indigenous voices and harm the environment. For these scholars, interconnection is not an abstract academic notion; it’s a lived reality that informs daily practices, rituals, and worldviews.

Third, indigeneity means being in relationship. Indigeneity is not static. Indigeneity is not just a fixed identity or a label; it’s an active engagement, a continuous act of reaffirming one’s relationship with the world, the community, and oneself. Moreover Indigeneity is a political stance that is in resistance and revolution to the forces of homogenisation, colonization and destruction that are at the heart of the metacrisis. It’s a dance of mutual recognition and respect, deeply rooted in histories, stories, and shared experiences. The ethos of radical care is an active, ongoing commitment to the welfare of all beings, recognizing the intrinsic value in each and the duty to protect and nurture.

Importantly Indigenous practices are always hyperlocal, contextual and related to a specific tapestry of biological and cultural diversity. In this sense, although we can extrapolate this to a set of orienting principles, the requirements of these always relate to attending to the context of relationships with which they deal – that are ecological, cultural and political. In sum, these more relational, animistic and lived paradigms emanating from Indigenous ontologies and explored in Post-Humanist scholarship, reshape our understanding of belonging and community, thus reorienting us towards a more inclusive, sustainable and communal future.

Embodied Indigeneity challenges Western paradigms around land

“Reforesting minds is a life plan: through reforesting our thoughts and decolonising the land, we hold the possibility of healing the colonial traumas within the landscape of our bodies. Our struggle is not only to reforest: our struggle is mainly to stop deforestation. Our struggle is not only to heal: our struggle is mainly to not get sick. Reforesting minds is a profound cry for a new relationship with nature. Founded in Indigenous cosmovisions, that drink in the complexity of the interactions between all that is alive, it manifests itself from our ancestry. Smīkra Wahikwa, ‘The future is ancestral’, as we say in the Xakriabá language.”

Sonia Guajajara & Célia Xakribá

When considering land, the Western ontological framework is anchored in notions of dominion and proprietorship. As described in the context, in the Western ontology that has cultivated capitalism and colonialism, land isn’t perceived as a living entity with which one nurtures a relationship. Rather, it’s seen as a commodity, a tangible asset subject to ownership, control, and exploitation. This perspective, rooted in utility and economic value, and has been prevalent not just in capitalist societies but also in Marxist and communist ideologies where settler occupation exists despite moving beyond individual ownership.

Indigenous ontologies present a vastly different understanding: land isn’t a possession but a relation. The bond with the land is rich, deeply ingrained, and founded on principles of reciprocity, respect, and care. It is not about extraction but about nurturing, understanding, and harmonizing with the environment. Land is kin. Enriched by ages of wisdom and symbiotic coexistence, Indigenous ontologies promote the sacredness of biodiversity and an overarching duty of care for all living entities.

The aim of this narrative intervention is to shift popular conceptions of land ownership towards the relational perspectives we find in Indigenous ontologies. As mentioned in the context, land is a key lever in transitioning out of the polycrisis towards post-capitalist relations. Land is a transition pathway. But how do we do this?

Moving forward: Justice plus onto-shift

This document sketched out how Indigenous ways of thinking and knowing provide inspiration for the ontological shift needed to move beyond the idea of land ownership. An ontological shift is a shift in the very ways we view, understand, sense, relate and engage with the word. In the policy world, the onto-shift relates to the idea of the “Overton Window”, or “window of discourse” which is a descriptive model for understanding how ideas in society change over time and influence politics. In simple terms, an ontological shift (towards ontologies of relationality) widens the window of discourse in the public sphere, which over time, makes the radical become common sense for the public. The radical in this context is to understand land as a relation, not a privatized resource to be commodified.

As discussed in the narrative analysis section, to change culture and fundamentally shift our relationship towards land, we follow the guiding strategy of “justice plus an ontological shift”.

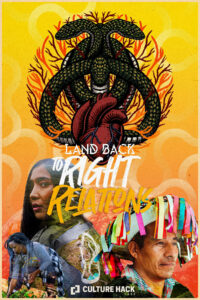

Justice relates to the important demands of activist communities that are rooted in decolonial discourse, asking for reparations and retribution. “Land Back” is the predominant narrative to achieve justice in the realm of land. “Land Back” is a contemporary Indigenous-led movement advocating for the return of Indigenous lands to Indigenous peoples, grounded in the recognition of historical and ongoing injustices related to the dispossession and colonization.

Ontological shift relates to the relational ontologies within Indigenous perspectives that we have sketched out as guiding inspiration for the reframe in this document. “Right Relations” is the key narrative here when it comes to land. “Right relations” align with the “all my relations” philosophy found in numerous Indigenous cultures. This philosophy underscores the interdependence of all beings, emphasizing our duty and mutual exchange within relationships.

Justice plus an ontological shift is a strategy that marries the decolonial justice demands of social movements to a concurrent shift in ontology (ways of seeing, knowing, sensing and being in this world) which is needed to achieve true justice. As Philosopher Bayo Akomolafe has argued: “Demands for social justice may get us a seat at the table, but they will never let us leave the house of modernity”. To leave the house of modernity, we need new ontologies.

In sum, we have outlined how relation to land represents a transition pathway out of the polycrisis and towards post-capitalist realities. Lenses of Indigeneity provide inspiration for the ontological shift needed alongside demands for decolonisation and reparations among Indigenous and broader social movements. In other words, this narrative intervention will contribute to achieving both justice (“land back”) and an onto-shift (“right relations”): “land back to right relations”.

Footnotes

- Ontology is the domain of being, what we assume to exist or what it means to exist, while epistemology is the domain of truth or validity, and therefore knowing. Indigenous perspectives, in all their diversity offer fundamentally different ways of knowing and being, ways that continue to be the best stewards of biodiversity and cultural antidotes to the metacrisis. In this reflection, we require a deep shift in both what we consider to be the nature existence and also what we consider to be true. (cf.) Bollier, D., & Helfrich, S. (2019). Free, fair, and alive: The insurgent power of the commons. New Society Publishers

- Trask, Haunani-Kay. “From a Native Daughter: Colonialism and Sovereignty in Hawai’i”. 1993; Deloria Jr., Vine. “Custer Died for Your Sins”. 1969; Alfred, Taiaiake. “Wasáse”. 2005

- LaDuke, Winona. “All Our Relations”. 1999

- Coulthard, Glen. “Red Skin, White Masks”. 2014.Highlights the systemic nature of colonial power structures and critiques the Canadian state’s relationship with Indigenous peoples.

- TallBear, Kim. “Native American DNA”. 2013. critiques the use of genetic testing to determine Native ancestry, challenging Western conceptions of identity.

- Yang, K. Wayne. “A Third University is Possible”. 2017.

- Katherin Yusoff refers to the On-going colonial present indicating the on-going benefits that accrue to capital-holders and colonial settlers through the structural arrangements of capitalist modernity.

Yusoff, K. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. University of Minnesota Press. 2018 - Akomolafe, Bayo. “These Wilds Beyond Our Fences”. 2017.Examines the nature of boundaries and the importance of community, tying into themes of land, identity, and indigeneity; Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. “Decolonizing Methodologies”. 1999

- Mbembe, Achille. “On the Postcolony”. 2001.analyzes postcolonial African identities, providing insights into the complexities of reclaiming identity after colonization.

- Zoomers, Annelies. Kaag, Mayke. The global land grab as modern day corporate colonialism. The Conversation. 2014

- Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Editions, 2013

- Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. Decolonization is not a metaphor. A clarion call to recognize the tangible implications of decolonization beyond mere rhetoric

- Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance. Simpson explores the importance of relationality in Indigenous cultures and their acts of resistance against colonial structures

- The Enlightenment describes a European intellectual movement in the Late Modern period (17th, 18th and 19th centuries) where the ideology of rationalism (the use of reason to gain knowledge) was developed.

- Ladha, A. and Kirk, M. (2016). Seeing Wetiko: On Capitalism, Mind Viruses, and Antidotes for a World in Transition. Kosmos Journal.

- Post-Humanism is a philosophical perspective that criticizes and moves beyond the human-centrism of western thought established during Greek Antiquity which has always excluded naturalized, gendered and racialized Others (animals/nature, women, the “native” respectively). Posthumanism centers “Life” in all its forms and strives to dissolve binaries (nature vs culture; self vs other, etc); . Braidotti, R., & Hlavajova, M. (Eds.). (2018). Posthuman glossary. Bloomsbury Publishing

- Todd, Z. (2016). An indigenous feminist’s take on the ontological turn:‘Ontology’is just another word for colonialism. Journal of historical sociology, 29(1), 4-22; Lovelock, J. E. (1972). Gaia as seen through the atmosphere. Atmospheric Environment, 6(8), 579–580; Lovelock, J. E., Margulis, L. (1974). Atmospheric homeostasis by and for the biosphere: The Gaia hypothesis. Tellus, 26(1–2), 2–10

- Gorzelak, M. A., Asay, A. K., Pickles, B. J., Simard, S. W. (2015). Inter-plant communication through mycorrhizal networks mediates complex adaptive behavior in plant communities. AoB Plants

- Deloria, Vine Jr. God is Red: A Native View of Religion. This work emphasizes the distinctiveness of Indigenous religious views and their interconnection with the natural world

- Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, 2016

- Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance. Simpson explores the importance of relationality in Indigenous cultures and their acts of resistance against colonial structures

- Plumwood, Val. Feminism and the Mastery of Nature. Routledge, 1993

- Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. Decolonization is not a metaphor. This critical examination of decolonization emphasizes the tangible, active commitments required for genuine change

- hooks, bell. Belonging: A Culture of Place. Routledge, 2008.

- Shiva, Vandana. Staying Alive: Women, Ecology, and Development. Zed Books, 1988

- Cajete, Gregory. Native Science: Natural Laws of Interdependence. An exploration of the Indigenous perspective on interconnectedness and the natural world

- Locke, John. Second Treatise of Government. Delineates Western conceptions of property and ownership.

- Harvey, David. The New Imperialism. Examines the concept of ‘accumulation by dispossession’, highlighting the commodification of land and resources

- Descartes, René. Meditations on First Philosophy. Descartes’ work encapsulates the Western emphasis on individual reasoning and mastery over nature. The Enlightenment era celebrated human reason, often placing humanity above nature, leading to dominion over the natural world.

- Marx, Karl. Capital, Volume 1. While Marx critiques the commodification of land and labor in capitalist societies, it’s important to note that settler occupation and the notion of land as a commodity can persist beyond capitalist paradigms, as discussed by Tuck and Yang.

- Cajete, Gregory. Native Science: Natural Laws of Interdependence

- Deloria, Vine Jr. God is Red: A Native View of Religion. Explores Indigenous views of land as sacred and alive

- Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance

- Through this understanding biodiversity is entangled and interdependent with cultural diversity.

- Coulthard, Glen Sean. Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition

- Bollier, D., & Helfrich, S. (2019). Free, fair, and alive: The insurgent power of the commons. New Society Publishers

- https://www.postcapitalistphilanthropy.org/

- https://landback.org/

- https://www.ourlivingwaters.ca/right_relations

- Ladha, Alnoor, and Lynn Murphy. “Post Capitalist Philanthropy: Healing Wealth in the Time of Collapse.” (2022)