Deep Dive: Culture and the Anthropocene

Contextualizing the Anthropocene

The term ‘culture’ has its roots in the term ‘cultivation of the soul’ (cultura anima), and is meant to signify the cultivation of the human condition to a noble or highest state. Through the Romantic and Enlightenment eras, this term came to mean the development of a community towards the highest levels of human potential. In contemporary terms, it has come to indicate the ideological disposition and social practices of a community, and as it pertains to the arts, culture and aspirations of that community.

Therefore a traditional definition of Culture could be:

Culture is a social domain that emphasizes the practices, discourses and material expressions of a community. It determines the social meaning of a life held in common.

However in our current context, what geologists call the Anthropocene , we are interested in a far more rich and complex understanding of what Culture is and what it does. As shown in Anthropogenic Effects:

- Although there is evidence that we can measure anthropogenic effects from pre-industrial times, we see the greatest anthropogenic effects from the beginning of the industrial revolution.

- Thereafter, with the advent of increasing consumption by the global North, we have seen an escalating anthropogenic impact in the last 50 years (1960, onwards)

- The global North is responsible for 92% of the contribution to the climate catastrophe in terms of historical emissions and material footprint.

- In this period we see the emergence of new social and cultural systems (e.g, globalization, neoliberalism and social dictatorships) that give warrant to rampant resource extraction and ecological destruction, exponential economic inequality and poverty.

Therefore we are inquiring into the cultural systems that have birthed and sustained the Anthropocene. In contrast to its initial meaning of ‘the evolution of the human condition’ we can see that Culture has a more pernicious implication for our evolution. As Terrence McKenna points out:

“Culture is for other people’s convenience and the convenience of various institutions, churches, companies, tax collection schemes, what have you. It is not your friend. It insults you. It disempowers you. It uses and abuses you. None of us are well-treated by culture.”

This echoes the definition of culture proposed by many decolonial thinkers writing about the harmful uses of culture.

Therefore, for the purposes of our inquiry we can develop a more ‘contextually relevant’ working definition of Culture:

Culture refers to the normative values and belief systems that coordinate human activity.

Through these normative values, culture enacts ideological models that give meaning to how we understand ourselves and our place in the world. These ‘systems of meaning’ make implicit distinctions about social, political and ecological categories such as nature/culture, subject/object, knower/object-to-be-known, human/non-human, self/other. As the anthropologist Clifford Geertz famously stated, “Man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun.” Culture is not inherently given or simply sui generis. It is a social/cultural/political construct that some, more than others, have a disproportionate responsibility in creating and benefiting from, although everyone affected by it contributes to it. Therefore, culture is both constructed and emergent, as well as felt/lived/experienced and invisible simultaneously.

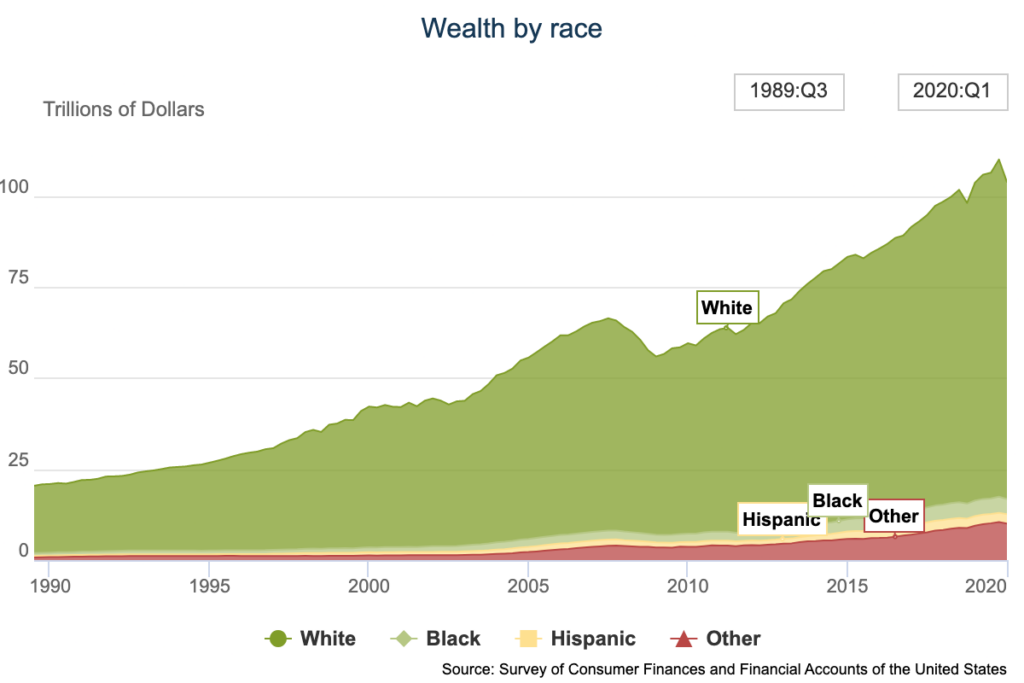

We can ascertain which categories are prioritized by a given culture by looking at the social, political and ecological outcomes the cultural system produces. For example, let’s examine the dominant culture of the United States vis-a-vis race and the distinction between white/non-white. In 2010 in the US, 40% of the prison population was made up of black people although they only made up 13% of the entire population. Additionally, in the same year, 60.7% of household wealth belonged to white households while black households owned only 3.8%. From this, it would be a fair inference that this cultural context prioritizes the normative category of “white” and in this prioritization it also deprioritises that which is “not white” through incarceration and impoverishment. Therefore we can gain insight into what normative values a culture holds by making empirical observations within its context.

Now let’s move to a global scale vis-a-vis the climate. As we have seen in Anthropogenic Effects, the ‘culture of the Anthropocene’ is one that prioritizes the unbridled conquest of the Global North in the ‘self-realization’ of its subjects. Moreover as Braidotti explains, this ‘subject’ is never a truly neutral category:

“…not all humans are equal and the human is not at all a neutral category. It is rather a normative category that indexes access to privileges and entitlements. Appeals to the “human” are always discriminatory: they create structural distinctions and inequalities among different categories of humans. Humanity is a quality that is distributed according to a hierarchical scale centered on a humanistic idea of Man as the measure of all things. This dominant idea is based on a simple assumption of superiority by a subject that is: masculine, white, Eurocentric, practicing compulsory heterosexuality and reproduction, able-bodied, urbanized, speaking a standard language. This subject is the Man of reason that feminists, anti-racists, black, Indigenous, postcolonial and ecological activists have been criticizing for decades.”

Taking this into account, perhaps the first clear assertion that we can make about Culture is that it is not always evolutionary (i.e. there is not a neat, tidy progressive narrative pointing to greater refinement, complexity, etc.). Rather, culture delineates a set of distinctions, assumptions, norms, beliefs about the world. At this juncture in our shared history it is essential that we develop ways to critically assess cultural systems, and in so doing find ways to evolve them.

The Development of Culture

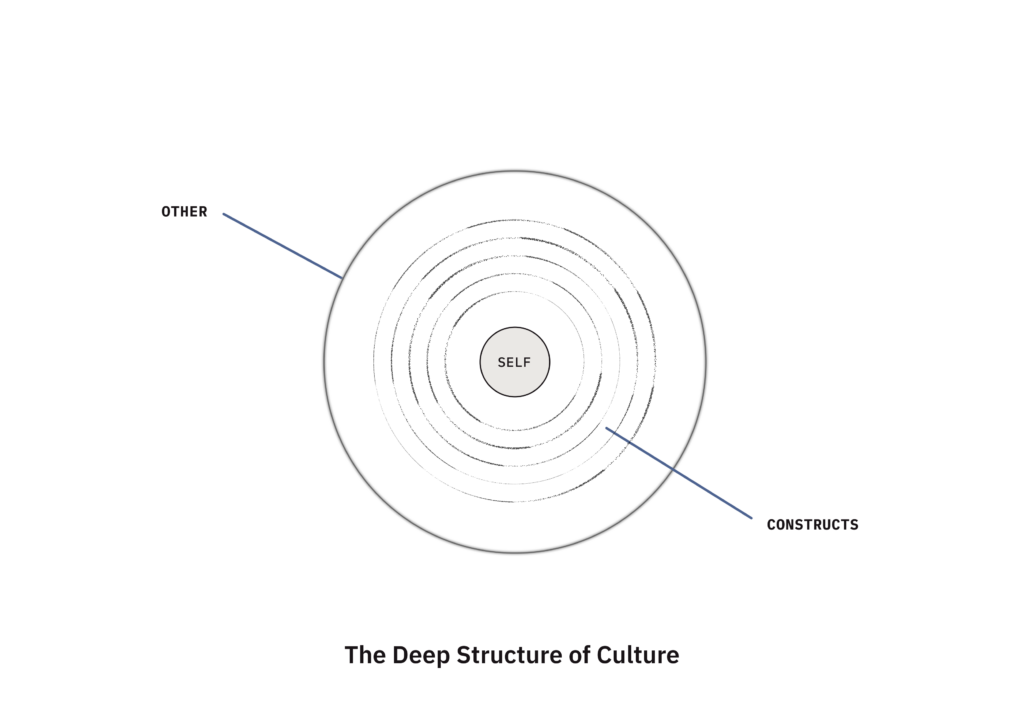

The fundamental unit of Culture is the Self (or absence of self) and its relationship to Other, and we can ‘measure’ a Culture by critically assessing this unit in terms of its relationship to that Other (that which is not Self). The resolution to the ‘problem of culture’ lies in the evolution of the Self and its process of self-reflection towards a redefinition of Self in terms of narratives of radical-relationality, belonging, interdependence and interbeing – in order to create more resilient and life-centric cultural systems.

The basis of Culture is a generative model describing the relationship between Self and Other. Any cultural model holds implicit understandings of what constitutes Self (including the absence of Self or relationality as Self). This relationship is mediated by constructs that define the world through this lens of Self – this includes moral judgements, truth claims, value determinations, ontological lenses and theoretical models of reality.

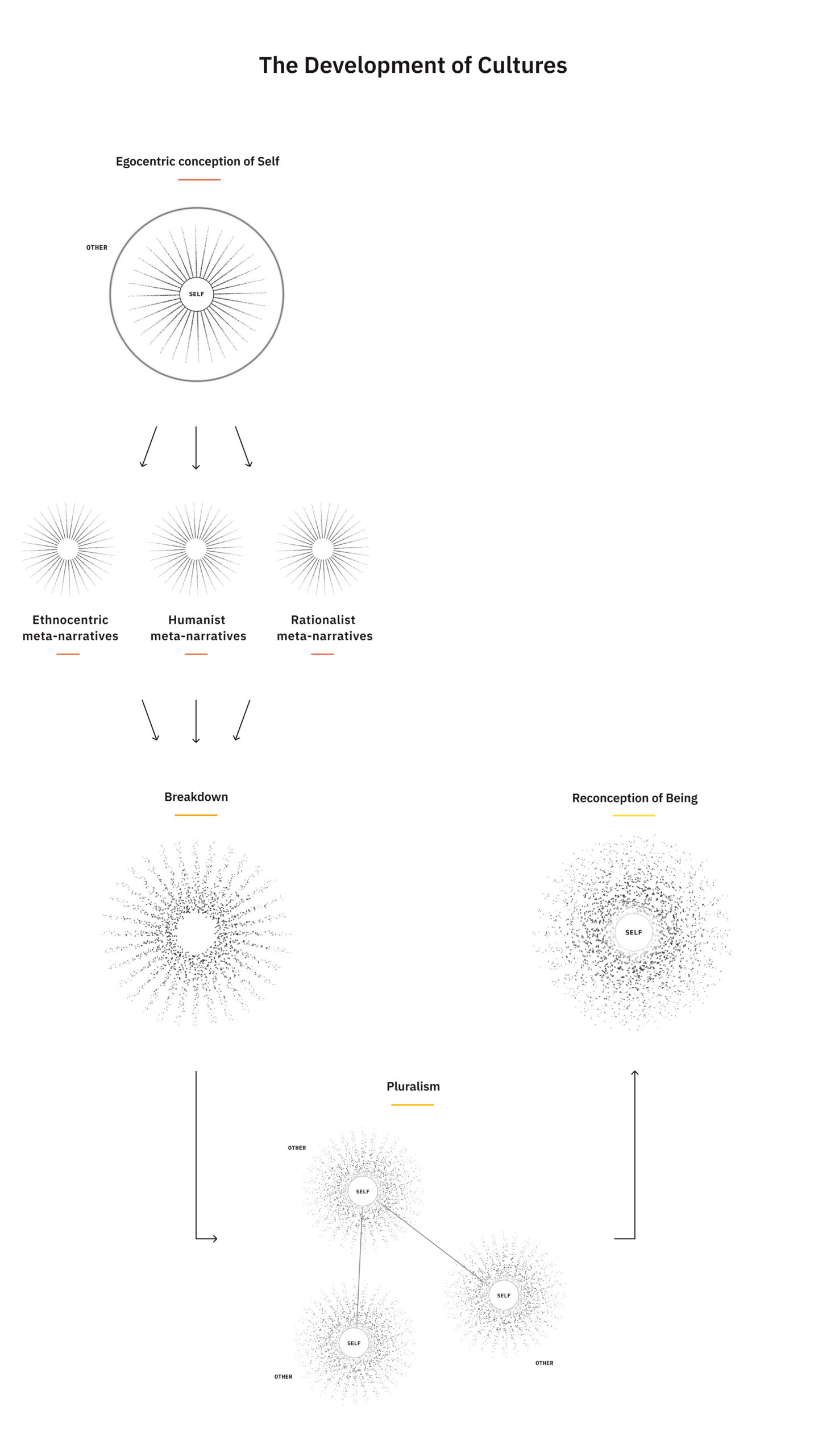

This model of Culture provides a pathway to better understanding the dominant Anthropocentric cultural forms. Below are four predominant meta-narratives for organizing society determined through the triangulation of Self, Other and cultural constructs.

| Meta-narrative | Constructs | Conception of Other |

| Ethnocentric | Convention and tradition of in-tribe determines value/truth. | Outside of tribal and historical convention. |

| Humanist | The ideals of freedom and liberty for (certain) humans determines value/truth. | Outside the human in-group. |

| Rational | Instrumental models of reality that can be determined cognitively are valuable/true. | Outside the technical and rational models of cognition. |

| Pluralist | Acceptance of multiple values and positions of truth, determined by the subjective limitations to contain pluralities. | Singular positions of truth. |

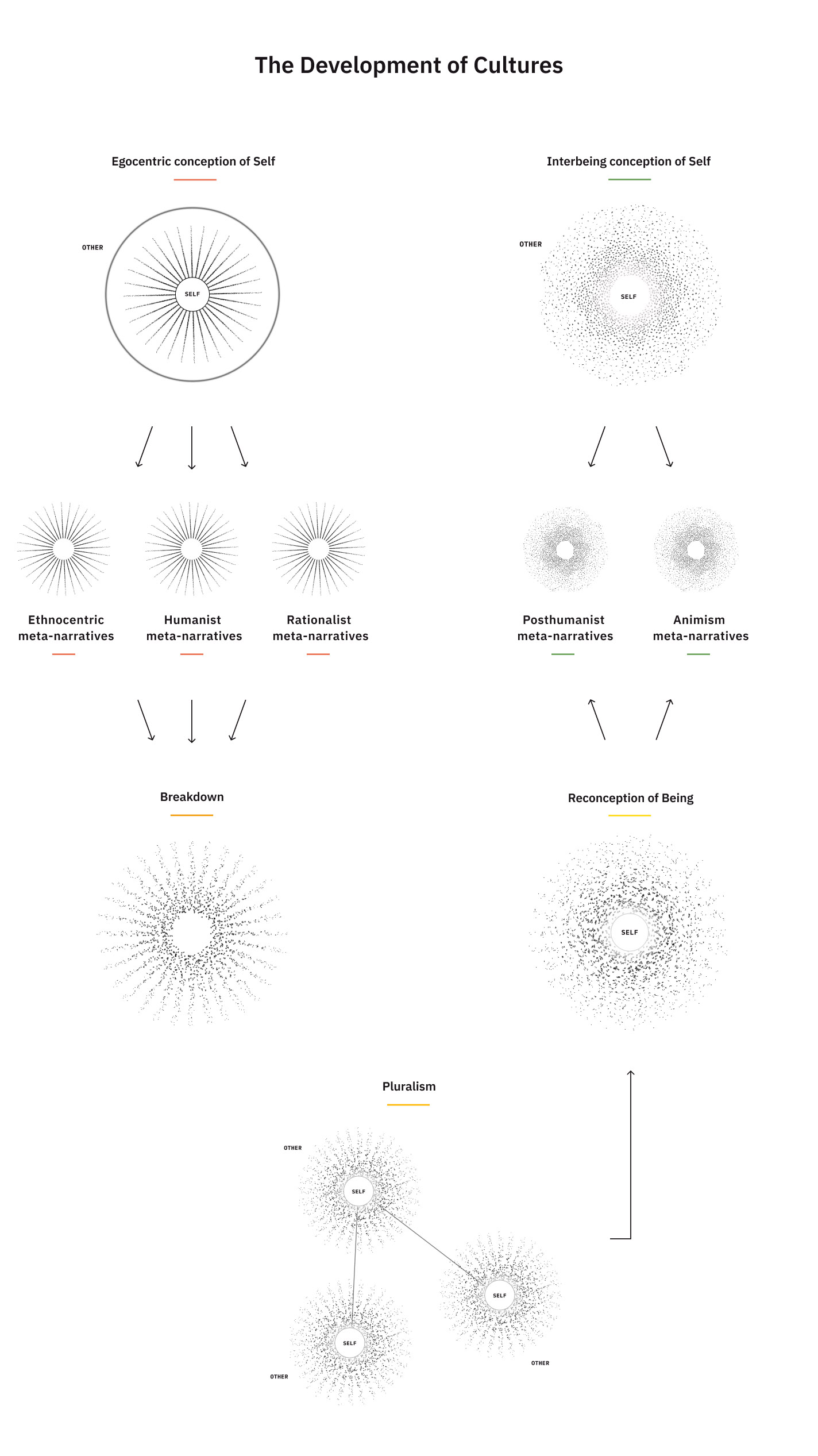

These four dominant cultural meta-narratives – Ethnocentrism, Humanism, Rationalism and Pluralism – are not exhaustive, but rather are indicative of specific stages of Anthropocentric culture, which thrives on individualism. All four of these meta-narratives prioritize egocentric subjectivity and are rooted (to varying degrees) in ethnocentric exceptionalism. For example, although the humanist and rationalist movements were partly born out of a critique of ethnocentric logic (especially the dominant Christian model of religious tribalism), they still reified the Self as the primary unit of subjective experience, and defined the Self as the category, ‘white, male European’. Since World War II, an ongoing dissatisfaction of these two meta-narratives have resulted in a more pluralistic paradigm, which of course, has also resulted in a bifurcation of nationalist, xenophobic reactions (e.g. European Community versus Brexit). Although pluralistic ontologies are supporting a reconception of the Self-Other-Construct triangulation, pluralism still lacks a defining point of view, an overarching moral philosophy, and a cosmology that cultivates a reconception of being and supports our collective evolution towards a more relational understanding of the self.

The archetypal development trajectory of the dominant Anthropocentric culture will continue to re-create the fundamental error of separation (separation of self vs other and separation from nature) until we “hack” the dominant conception of the Self-Other-Construct trinity.

These alternative meta-narratives do not need to be created ex nihilo. There is a rich tradition of counter-narratives in epistemologies of the global South, including social movements and Indigenous communities. These narratives share a trans-personal sense of Self that is in radical relationality to both the human and more-than-human worlds, both the seen and unseen realms. They share a life-centric approach based on kinship with the living world, reciprocity, generosity, regeneration, consent, dialogue and solidarity.

Two examples of this are the ancient cosmologies of animism (seeing the world and its constitutive parts as living, relational and dialogic) and post-humanism (thinking/feeling beyond human gaze, care and concern). There are many other meta-narratives we could include here including buen vivir from Latin American traditions, ubuntu (”I am who I am through you”) from the Bantu African cosmologies, etc. What these trans-personal, life-centric narratives hold in common is an ethic of interbeing. This goes beyond interdependence into a radical re-definition of Self through Other, breaking the binary of Western, dualistic, rationalistic thinking.

We believe that part of the cultural evolutionary process requires an understanding of the deep logic, narratives, cultural codes and belief systems of the dominant system; researching and synthesizing life-centric alternatives, especially those rooted in Earth-centric, symbiotic cultures; and testing and iterating new/emerging/ancient narratives in realtime to expose, disrupt and shift cultural assumptions to create new/ancient/emerging narrative spaces for possibility, transformation, restoration and justice.

For further reading, here is a list of references.

Footnotes

- Anthropocene is a term from the natural sciences that became widely used in the humanities and social sciences. It follows the Holocene (an epoch that started around 12000 years ago during the last glacial retreat, in which the stable and warm climate provided ideal conditions for the invention of agriculture: the Neolithic or Agricultural Revolution). There is disagreement as to when exactly the Anthropocene started: e.g. 8000 years ago when farming and agriculture became widespread (Ruddiman, 2003); or the peak of the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century (Steffen et al, 2011). Acknowledging its beginnings as the Industrial Revolution implies historical responsibility for industrialized countries (Chakrabarty, 2018). See an overview of the Anthropocene or read key texts:. Chakrabarty Dipesh, The Climate of History: Four Theses. Critical Inquiry 35(2): 197-222 (2009); Chakrabarty, Dipesh. “Anthropocene time.” History and Theory 57, no. 1 (2018): 5-32; Zalasiewicz, Jan et al. “Are we now living in the Anthropocene?” GSA Today 18 (2): 4–8 (2008) see further reading page for more information.

- See reference 3 to read more about the cultural systems (or “fragile societies”) that have birthed and sustained the anthropocene. Learn about globalization through a decolonial lens in this free online course (with lectures and resources). Modules 1) The making of the modern world; and 3) Colonial global economy are especially relevant. Read short overviews on Racial Capitalism; or Capitalism and neoliberalism. Read more: Graeber, D., & Wengrow, D. (2021). The dawn of everything: A new history of humanity. Penguin UK; Hickel, J. (2017). The divide: A brief guide to global inequality and its solutions. Random House; Hickel, J. (2020). Less is more: How degrowth will save the world. Random House; Chomsky, N. (1999). Profit over People: Neoliberalism and Global Order Seven Stories Press; Luxton, M. and Braedley, S. (2010). Neoliberalism and Everyday Life. McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP; Springer, S. (2012). Neoliberalism as Discourse: Between Foucauldian Political Economy and Marxian Poststructuralism. Critical Discourse Studies, 9(2): 133-147; Harvey, D. (2005). A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford University Press.

- The cultural systems or “fragile societies”, include ethnocentric, humanist, rationalist, and even pluralistic cultural systems – as opposed to “resilient societies” (see reference 13). These societies – albeit to differing degrees – promote an ego-centric conception of self, as opposed to an “interbeing/relational” conception of self (see reference 25). This greedy, excessive and selfish nature of the west is named “wetiko” by North American First Nations (Ladha and Kirk, 2016). Such societies have birthed and sustained the Anthropocene for various reasons, including: the dualistic logics of thought stemming from a Cartesian dualism established during the Enlightenment that must always exclude a devalued Other (see reference 6); their exclusionary ideas of who counts as Human; and their separation from nature in order to exploit it. Patel and Moore (2017) propose Cartesian dualism was even purposely created so that early capitalists could destroy the non-Anthropocentric perspectives that posed an obstacle to their exploitation and objectification of the natural world required by capitalism: dualism became am ontological justification for seeing nature and “native” as object and less than human – which legitimised ecocide, imperialism, and slavery. This coincided with the 16th century introduction of the printing press which represented the victory of the written “rational” language of the oppressor over oral traditions, which contributed to the marginalization of non-binary/non-anthropocentric Indigenous thought (ibid, 2017). See Mignolo, W D. (2011) Chapter: The Darker Side of Enlightenment: A Decolonial Reading of Kant’s Geography, in The darker side of Western modernity. Duke University Press; Dhawan, N. (Ed.). (2014). Decolonizing enlightenment: Transnational justice, human rights and democracy in a postcolonial world. Verlag Barbara Budrich. Patel, R., & Moore, J. W. (2017). A history of the world in seven cheap things. University of California Press; Anderson, B. (2020). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Routledge; Shlain, L (1998). The Alphabet Versus the Goddess: The Conflict Between Word and Image. Viking Press; Ladha, A. and Kirk, M. (2016). Seeing Wetiko: On Capitalism, Mind Viruses, and Antidotes for a World in Transition. Kosmos Journal.

- It is important to note that we are not talking about traditional Darwinian evolution, nor about evolution in terms of competition, but about the emergence of new forms of cooperation and coordination among humans is inspired by David Sloan Wilson and Lynn Margulis: read more or see Module 3. Cultural evolution refers to the idea that the development and transmission of symbolic thought, values, norms and ethical imperatives among humans shape their behavior and impact their evolutionary trajectory. Cultural evolution operates alongside genetic evolution, in which humans inherit not only genes (genotypes) but also cultural traits (symbotypes) that influence their behavior, and has led to the emergence of new forms of cooperation and coordination among humans. For Culture Hack Labs, cultural evolution involves guiding the evolutionary process of cultural change towards value systems that are in service of life – which is necessary for our and our planet’s survival.

- Terence Mckenna is a North American ethnobotanist, mystic and New Age philosopher_. Mckenna, T (1999) Culture is Not Your Friend; Mckenna, T (1999) What does it mean to be human in this cosmos?

- For example, see Fanon, F, (1961) The Wretched of the Earth; Mbembe, A (2005). On the Postcolony; Collins, P. H. (1990). Black Feminist Thought; Anzaldúa, G. E. (1987). Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza; Browse Culture Hack Lab’s curated content on the role of culture from a decolonial perspective.

- These (western) systems of meaning rely on binary oppositions (e.g nature/culture, self/other, rational/emotional, man/woman, modern/primitive, developed/undeveloped, advanced/backward, etc). Anthropologist Levi Straus (1977) established this dualism as the structure of basic human thinking and the building blocks of shared cultural meaning, and assumed his model was universal. This form of binary thinking is attributed to Enlightenment thinker Descartes and his separation of body and mind (Cartesian dualism). See postmodernist philosopher Derrida’s critical discussion of how one term is always given a more privileged position than its opposite, and the ‘logic of the negative other” in western thinking (Derrida, 1978; Morrison, 1994). Read more by exploring philosophies of “transcendence” (in which existence is divided into different realms, with one ruling over the other – e.g. European’s “transcended” above everything else) and how to move beyond this: postmodern philosophies of immanence in which all things share the same realm (Deleuze and Guattari, 1988). For a simple overview of binary/dualistic ways of thinking, see this one page explainer. This thinking structure is pervasive in “fragile” (see reference 3), not “resilient” societies which tend to be pre/non-dualistic (see reference 13). Levi Straus, Claude (1977) ‘Social Structure,’ Structural Anthropology, Volume; Peregrine books, Penguin, Harmondsworth; Derrida, Jacques., 1978. Writing and difference. University of Chicago press; Morrison, T., 1994. Playing in the dark: Whiteness and the literary imagination. New York: Vintage; Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Bloomsbury Publishing, 1988.

- Geertz, Clifford. Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture. Routledge, 2008.

- The idea that certain groups/classes disproportionately create and benefit from cultural construction relates to the concept of Neo-Marxist Gramsci’s idea of “cultural hegemony” which moves beyond the pure economism of traditional Marxism, and looks at how power is held not only in the means of production, but in culture/consciousness (or the “superstructure”). Importantly, he highlighted the role of popular culture as contributing to cultural creation (or counter-hegemonic cultures that always run against dominant power/”common sense”). Also see how culture is embodied and reproduced through Bourdieu’s notion of ”habitus”; and performed through Butler’s notion of “performativity” (2010). Hall, Stuart. “Gramsci’s Relevance for the Study of Race and Ethnicity.” Journal of communication inquiry 10, no. 2 (1986): 5-27; Gramsci, Antonio. “Prison Notebooks. Ed. Joseph A. Buttigieg.” Trans. Buttigieg and Antonio Callari. Vols (1992); Butler, J. (2010). Performative agency. Journal of cultural economy, 3(2), 147-161; Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. Stanford university press.

- Source: Sakala, L. (2014). Breaking Down Mass Incarceration in the 2010 Census: State-by-State Incarceration Rates by Race/Ethnicity; Prison Policy Initiative. Figures calculated with US Census 2010 SF-1 table P42 and the PCT20 table series. The disproportionate targeting of racialized communities is prevalent across the west. Further reading for the USA context: Alexander, M., 2012. The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. The New Press; Tonry, M.H., 2011. Punishing race: A continuing American dilemma. Oxford University Press; and Europe: Fassin, D., 2018. The will to punish. Oxford University Press. Also see how the disproportionate targeting of certain individuals/groups based on their ‘race’ intersects with other elements of identity/biography that are devalued/deprioritized by the hegemonic neoliberal culture, e.g: Class: Wacquant, L., 2009. Punishing the poor: The neoliberal government of social insecurity. Duke University Press; Gender: Bosworth, M., & Kaufman, E. (2012). Gender and punishment. Handbook of punishment and society, 186-204; Migration status: In Europe: Aas, K.F. and Bosworth, M. eds., 2013. The borders of punishment: Migration, citizenship, and social exclusion. Oxford University Press. For a framework to analyze these interlocking systems of disadvantage – see Kimberly Crenshaw’s “intersectionality” framework (summarized in Global Social Theory’s page here). Crenshaw, K (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stan. L. Rev., 43.

- Rosi Braidotti speaks from an explicitly “anti-humanist” position. She criticizes the humanism established in Classical Antiquity, developed through the European Renaissance and Enlightenment, used for European Colonialism, and embedded in the supposedly emancipatory politics of some movements, e.g. Liberal Feminism. She builds on the western philosophy that planted the seeds of anti-humanism (Nietzche, Heidegger and Foucault) as well as the more radical “postmodernist philosophies” (which she names “antihumaist philosophies”) such as anti-universalist Feminism; Post-colonial theory; and Poststructuralism – to arrive at her “post-human” position (see reference 22 for more details). Although Braidotti does recognise the strategic importance of humanism for some postcolonial scholars (e.g. Fanon; Said; Spivak). Braidotti, R. (2020) “We” are in this together, but we are not one and the same.” Journal of bioethical inquiry 17, no. 4: 465-469; Braidotti, R, (2013) The Posthuman, Polity; Nietzsche, F. (1882) The Gay Science; Heidegger, M (1947), Letter on Humanism; Foucault, M (1966). The Order of Things; Said, E. W. (2004). Humanism and democratic criticism. Columbia University. Read other post-colonial positions on the human, e.g. Sylvia Wynter, or Franz Fanon.

- These narratives of relationality and interbeing can be described as narratives of “Return”. “The Return” is an archetypical developmental phase marked by a growing realization of the interdependent self which represents a new evolutionary potential for Culture. Read more about the “Return” in our annex on the genesis of history here. The annex also provides more information on the developmental stages of cultural creation and outlines the role of the Self in history.

- Resilient or life-centric cultural forms (which include but are not limited to Animistic or Indigenous societies) refer to cultural systems that are pre/non-dualistic, in which the sphere of sociality includes a spectrum of seen and unseen living beings including plants, fungi, animals, and spirits (as opposed to “fragile” cultural forms, see reference 3). Nature and culture/society fuse into one another. See literature from Anthropology on multi-specism; perspectivism; and multi-naturalism to learn more – much of this came out of the “ontological turn” in Anthropology, in which the difference between cultures was no longer seen as a difference in worldview (multi-culturalism), but a difference in worlds (multi-naturalism) – which are all equally valid. See: Descola, P. (2013) Beyond nature and culture. University of Chicago Press – especially chapter 1: Configurations of Continuity; De Castro, E V (2007). “The crystal forest: notes on the ontology of Amazonian spirits.” Inner Asia 9, no. 2: 153-172; and De Castro’s (2004) lecture-series on the ontological turn and multi-naturalism: Cosmological Perspectivism in Amazonia and Elsewhere HAU: Masterclass Series; Ixchiu, A (2022). We are nature defending itself. Culture Hack Labs Issue 01. See Culture Hack Labs (2022) “Issue 03: Milpamérica, living solutions to the Climate Crisis” to explore how Indigenous and Black people inhabiting Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador are putting forward their ways of living to push back against the extermination of life.

- Ethnocentrism involves an evaluation of another culture based on preconceptions developed from the standards/conventions of one’s own culture. See how it interacts with different constructs such as race, ethnicity, or nation: Brubaker, R. (2009). Ethnicity, race, and nationalism. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 21-42; Bizumic, B., & Duckitt, J. (2012). What is and is not ethnocentrism? A conceptual analysis and political implications. Political psychology, 33(6), 887-909; Tambiah, S. J. (1996). The nation-state in crisis and the rise of ethnonationalism. The politics of difference: Ethnic premises in a world of power, 124-143

- Humanism was established during Classical Antiquity and developed during the European Renaissance and Enlightenment periods in which man was renewed as the “measure of all things”. Anthropos (human in Ancient Greek) or “human” (from Latin) were defined in relation to what they were not: either a god, an animal, or who the Greeks considered “barbarians” at that time. Read more: Davies, T. (2008). Humanism. Routledge; and a critique through the lens of anti/post-humanism: Braidotti, R, (2013) The Posthuman, Polity.

- Rationalism, developed during the 17th and 18th century Enlightenment, is the use of reason to gain knowledge. Read more through Foucault’s analysis of power and construction of truth. Foucault, M. (1975). Discipline and punish; Bristow, W, (2017) “Enlightenment”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Pluralism is a recognition, affirmation and aspiration of diversity and peaceful coexistence of different traditions, lifestyles, ideas and values (e.g. Interculturalism in Canada, multiculturalism in the UK). While there are attempts to make pluralism more inclusive: e.g. see critical multiculturalism, the frameworks often still rely on ecocentric conceptions of the self, not radical relationality. Pedersen, N. J. L. L., & Wright, C. (2012). Pluralist theories of truth. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Mason, E. (2006). Value pluralism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Kastoryano, R. (2018). Multiculturalism and interculturalism: redefining nationhood and solidarity. Comparative Migration Studies, 6(1), 1-11; Mack, E. (1993). Isaiah Berlin and the quest for liberal pluralism. Public Affairs Quarterly, 7(3), 215-230.

- Evolutionary development literature: Beck, D. E., & Cowan, C. C. (2014). Spiral dynamics: Mastering values, leadership and change. John Wiley & Sons.

- See reference 2 on the cultures that have birthed and sustained the anthropocene in which there has been a separation of self vs other and separation from nature through other binary logics (e.g. culture vs nature).

- Counter narratives in the epistemologies of the global South (e.g. key texts from Latin American, Asian and African scholars): Mignolo, W, D (2020) Epistemic Disobedience, Independent Thought and Decolonial Freedom; Rivera Cusicanqui, S. (2012), Ch’ixinakax utxiwa: A Reflection on the practices and discourses of decolonisation, The South Atlantic, 111(1): 95-109 & see her Global Social Theory page.; Spivak, G C (2003) Can the subaltern speak?; Mbembe, Achille (1992) Provisional notes on the postcolony. See how environmental movements have attempted to integrate Indigenous counter-epistemologies/ontologies (including reassessing notions of time): Wright, S., Suchet-Pearson, S., Lloyd, K., Burarrwanga, L., Ganambarr, R., Ganambarr-Stubbs, M, Maymuru, D. (2020). Gathering of the clouds: attending to indigenous understandings of time and climate through songspirals. Geoforum, 108, 295-304; Colchester, M. (2004). Conservation policy and indigenous peoples. Environmental Science & Policy, 7(3), 145-153; Mistry, J., & Berardi, A. (2016). Bridging indigenous and scientific knowledge. Science, 352(6291), 1274-1275; McGregor, D. (2004). Coming full circle: Indigenous knowledge, environment, and our future. American Indian Quarterly, 28, 385–410. And see an example from Culture Hack’s practice of how animistic, counter-hegemonic narratives have been used in Mexico to win environmental campaigns – Ladha, A and Sandoval, L, 2019. Campaign to defend Mexico’s sacred lake changes global activism. Truthout.

- Animism is both a concept and a way of relating to the world – attributing a quality of being “animate” to a large range of human and non-human beings in the world, such as the environment, animals, plants, spirits, and forces of nature like the sun, moon, winds or oceans. For example, read about “Sila”, or life force, which has been an organizing principle for Inuit communities for thousands of years (Todd, 2016). A more recent iteration of Animism is Gaia theory (Lovelock and Margulis, 1974) – which popularized the idea of earth as an animate, living and self-regulating organism. Western theories such as Gaia, and animistic/indigenous cosmologies have also been “reinforced” by scientific developments shedding light on the self-organizing/”smart” structure of living matter, for example, the symbiotic relationship between the soil, fungi, and plants show that how trees/plants communicate through their roots and vast underground networks of mycelium (Gorzelak et al., 2015). The earth is indeed alive and animistic/Indigenous forms of knowledge are more and more seen as “empirically accurate”. Read an overview: Swancutt, K. A. (2019). Animism. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology, 1-17; Bird-David, Nurit. (1999) ““Animism” revisited: personhood, environment, and relational epistemology.” Current anthropology 40, no. S1; Todd, Z. (2016). An indigenous feminist’s take on the ontological turn:‘Ontology’is just another word for colonialism. Journal of historical sociology, 29(1), 4-22; Lovelock, J. E. (1972). Gaia as seen through the atmosphere. Atmospheric Environment, 6(8), 579–580; Lovelock, J. E., Margulis, L. (1974). Atmospheric homeostasis by and for the biosphere: The Gaia hypothesis. Tellus, 26(1–2), 2–10; Gorzelak, M. A., Asay, A. K., Pickles, B. J., Simard, S. W. (2015). Inter-plant communication through mycorrhizal networks mediates complex adaptive behavior in plant communities. AoB Plants.

- Post-humanism (not to be confused with trans-humanism that is still humanist because it privileges human capacities) is Life-centric (or, Zoe-centric) because it centers life in all its forms (both human and non-human, seen and unseen beings). There are different variations of posthumanism due to different intellectual geneaologies (e.g., Rosi Braidotti’s critical post-humanism developed out of anti-humanist Philosophy/Cultural Theory Vs Bruno Latour’s analytic post-humanism developed out of Science and Technology Studies). Posthumanism is not only critical, but also constructive (or creative – Braidotti): it aims to build new alternatives to humanism by developing new concepts/vocabularies to enable us to move beyond western binaries. Two important examples are 1) Rosi Braidotti’s call for a Life/Zoe-centric Egalitarianism and 2) Karen Barad’s “onto-ethico-epistemology” – which argues that what is in the world (ontology) and how we know what is in the world (epistemology) can not be separated as two distinct realms that do not affect one another – and the implications of this entanglement on how we should engage in the world (ethics). Much of this literature developed out of the 21st century “material turn” and the Neo/New-materialism of ecocentric scholars attempting to decentre the human and analyze relations, or “intra-actions” (Barad, 2007) between humans and nonhumans (e.g. animals, bacteria, rocks, etc). Material/matter is understood as “vital” (Barad, 2007), vibrant, alive, relational, plural, open, complex and contingent. Read more: Latour, B. (2012). We have never been modern. Harvard university press; Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the Trouble. Duke University Press; Braidotti, R., & Hlavajova, M. (Eds.). (2018). Posthuman glossary. Bloomsbury Publishing; Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway. Duke University Press; Sencindiver, S. Y. (2017). New materialism. Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory, 1565; or read an overview: new materialism (on Global Society Theory); Ladha, A and Akomolafe, B, (2017) Perverse particles, entangled monsters and psychedelic pilgrimages: Emergence as an onto-epistemology of not-knowing. Ephemera Journal.

- Read more about Buen Vivir: its connection to indigenous cosmologies, its inspirational content for social movements, and how “the subject of wellbeing is not the individual, but the individual in the social context of their community and in a unique environmental situation” (Gudynas, 2013). Gudynas, E. (2011). Buen Vivir: today’s tomorrow. development, 54(4), 441-447; The Guardian, (2013) Buen vivir: the social philosophy inspiring movements in South America; Mercado, J. (2017). Buen Vivir: A New Era of Great Social Change. Pachamama Alliance Blog.

- Read/listen to more about Ubuntu and how it may be a counterweight to rampant individualism or heal society/nature/self relations: Ogude, J, “I Am Because We Are”: the African Philosophy of Ubuntu; Le Grange, L. (2012). Ubuntu, ukama and the healing of nature, self and society. Educational philosophy and theory, 44(sup2), 56-67; Ramphele, M. (2020). Ubuntu: The Dream of a Planetary Community. In P. Clayton et al (eds.) The New Possible: Visions of Our World Beyond Crisis.

- The concept of a transpersonal/interbeing/relational self tends to be the prevalent conception of the self in resilient/life-centered cultural forms. Broadly speaking, the experience of the self falls into a division between between the ‘closed, individuated, autonomous, egocentric, “western” self and an open, relational, interdependent, sociocentric, “non-western” self’ (Hollan 1992, p.294; Taylor, 2007). Einstein, C and Ladha, A, (2020). Oppression, Interconnection and Healing. Kosmos Journal (read or listen). Thich Nhat Hanh’s teaching on “interbeing”: Naht Hanh, T. (1993). Interbeing: Fourteen guidelines for engaged Buddhism. Berkeley. CA: Parallax and a short video “To be means to interbe” (Plum Village); Hollan, D. (1992). Cross-cultural differences in the self. Journal of Anthropological Research, 48(4), 283-300; Taylor, C. (2007). A secular age. Harvard University Press.